Posts tagged ‘behavioral finance’

Experts vs. Dart-Throwing Chimps

Daniel Kahneman, a professor of psychology at Princeton University, knows a few things about human behavior and decision making, and he has a Nobel Prize in Economics to prove it. We live in a complex world and our brains will often try to compensate by using shortcuts (or what Kahneman calls “heuristics” and “biases”), in hopes of simplifying complicated situations and problems.

When our brains become lazy, or we are not informed in a certain area, people tend to also listen to so-called experts or pundits to clarify uncertainties. In the process of their work, Kahneman and other researchers have discovered something – experts should be listened to as much as monkeys. Frequent readers of Investing Caffeine understand my shared skepticism of the talking heads parading around on TV (read first entry of 10 Ways to Destroy Your Portfolio)

Here is how Kahneman describes the reliability of professional forecasts and predictions in his recently published bestseller, Thinking, Fast and Slow:

“People who spend their time, and earn their living, studying a particular topic produce poorer predictions than dart-throwing monkeys who would have distributed their choices evenly over the options.”

Most people fall prey to this illusion of predictability created by experts, or this idea that more knowledge equates to better predictions and forecasts. One of the factors perpetuating this myth is the rearview mirror. In other words, human’s ability to concoct a credible story of past events creates a false confidence in peoples’ ability to accurately predict the future.

Here’s how Kahneman describes the phenomenon:

“The idea that the future is unpredictable is undermined every day by the ease with which the past is explained…Our tendency to construct and believe coherent narratives of the past makes it difficult for us to accept the limits of our forecasting ability. Everything makes sense in hindsight, a fact financial pundits exploit every evening as they offer convincing accounts of the day’s events. And we cannot suppress the powerful intuition that what makes sense in hindsight today was predictable yesterday. The illusion that we understand the past fosters overconfidence in our ability to predict the future.”

Even when experts are wrong about their predictions, they tend to not accept accountability. Rather than take responsibility for a bad prediction, Philip Tetlock says the errors are often attributed to “bad timing” or an “unforeseeable event.” Philip Tetlock, a psychologist at the University of Pennsylvania did a landmark twenty-year study, which was published in his book Expert Political Judgment: How Good Is It? How Can We Know? (read excellent review in The New Yorker). In the study Tetlock interviewed 284 economic and political professionals and collected more than 80,000 predictions from them. The results? The experts did worse than blind guessing.

Based on the extensive training and knowledge of these experts, many of them develop a false sense of confidence in their predictions. Or as Tetlock explains it, “They [experts] are just human in the end. They are dazzled by their own brilliance and hate to be wrong. Experts are led astray not by what they believe, but by how they think.”

Brain Blunders and Stock Picking

The buyer of a stock thinks the price will go up and the seller of a stock thinks the price will go down. Both participants engage in the transaction because they believe the current stock price is wrong. The financial services industry is built largely on this phenomenon that Kahneman calls an “illusion of skill,” or ability to exploit inefficient market pricing. Relentless advertisements and marketing pitches continually make the case that professionals can outperform the markets, but this is what Kahneman found:

“Although professionals are able to extract a considerable amount of wealth from amateurs, few stock pickers, if any, have the skill needed to beat the market consistently, year after year. Professional investors, including fund managers, fail a basic test of skill: persistent achievement…Skill in evaluating the business prospects of a firm is not sufficient for successful stock trading, where the key question is whether the information about the firm is already incorporated in the price of its stock. Traders apparently lack the skill to answer this crucial question, but they appear ignorant of their ignorance.”

For the few managers that actually do outperform, Kahneman assigns luck to the outcome, not skill:

“For a large majority of fund managers, the selection of stocks is more like rolling dice than like playing poker. Typically at least two out of three mutual funds underperform the overall market in any given year…The successful funds in any given year are mostly lucky; they have a good roll of the dice.”

The picture for individual investors isn’t any prettier. Evidence from Terry Odeam, a finance professor at UC Berkeley, who studied 100,000 individual brokerage account statements and about 163,000 trades over a seven-year period, was not encouraging. He discovered that stocks sold actually did +3.2% better than the replacement stocks purchased. And this detrimental impact on performance excludes the significant expenses related to trading.

In response to Odean’s work, Kahneman states:

“It is clear that for the large majority of individual investors, taking a shower and doing nothing would have been a better policy than implementing the ideas that came to their minds….Many individual investors lose consistently by trading, an achievement that a dart-throwing chimp could not match.”

In a future Odean paper titled, “Trading is Hazardous to your Wealth,” Odean and his colleague Brad Barber also proved that “less is more.” The results showed the most active traders had the weakest performance, and those traders who traded the least had the best returns. Interestingly, women were shown to have better investment results than men.

Regardless of whether someone is listening to an expert, fund manager, or individual investor, what Daniel Kahneman has discovered in his long, illustrious career is that humans consistently make errors. If you are wise, you will heed Kahneman’s advice by stealing the expert’s darts and handing them over to the chimp.

Wade W. Slome, CFA, CFP®

Plan. Invest. Prosper.

DISCLOSURE: Sidoxia Capital Management (SCM) and some of its clients own certain exchange traded funds, but at the time of publishing SCM had no direct position in any other security referenced in this article. No information accessed through the Investing Caffeine (IC) website constitutes investment, financial, legal, tax or other advice nor is to be relied on in making an investment or other decision. Please read disclosure language on IC “Contact” page.

The Pleasure/Pain Principle

The financial crisis of 2008-2009 was painful, not to mention the Flash Crash of 2010; the Debt Ceiling / Credit Downgrade of 2011; and the never-ending European saga. Needless to say, these and other events have caused pain akin to burning one’s hand on the stove. This unpleasant effect has rubbed off on investors.

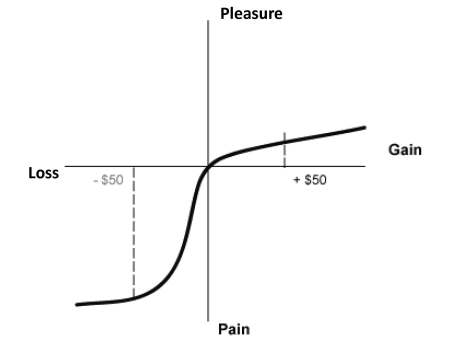

Admitting one has a problem is half the battle of conquering a challenge. A key challenge for many investors is understanding the crippling effects fear can have on personal investment decisions. While there are certainly investors who constantly see financial markets through rose-colored glasses (my glasses I argue are only slightly tinted), Nobel Prize winner Daniel Kahneman and his partner Amos Tversky understand the pain of losses can be twice as painful as the pleasure experienced through gains (see diagram below).

Said a little differently, faced with sure gain, most investors are risk-averse, but faced with sure loss, investors prefer risk-taking. Don’t believe me? Well, let’s take a look at some of Kahneman and Tversky’s behavioral finance work on what they called “Prospect Theory” (1979) – the analysis of decisions made under various risk scenarios.

In one specific experiment, Kahneman and Tversky presented groups of subjects with a number of problems. One group of subjects was presented with this problem:

Problem #1: In addition to whatever you own, you have been given $1,000. You are now asked to choose between:

A. A sure gain of $500

B. A 50% change to gain $1,000 and a 50% chance to gain nothing.

Another group of subjects was presented with this problem:

Problem #2: In addition to whatever you own, you have been given $2,000. You are now asked to choose between:

A. A sure loss of $500

B. A 50% chance to lose $1,000 and a 50% chance to lose nothing.

In the first group, 84% of the respondents chose A and in the second group, 69% of the respondents chose B. Both problems are identical in terms of the net cash outcomes ($1,500 for Answer A, and 50% chance of $1,000 or $2,000 for Answer B). Nonetheless, due the different “loss phrasing” in each question, Answer A sounds more appealing in Question #1, and Answer B sounds more appealing in Question #2. The results are irrational, but investors have been known to be illogical too.

In practical trading terms, the application of “Prospect Theory” often manifests itself via the pain principle. Due to loss aversion, investors tend to cash in gains too early and fail to allow their winning stocks to run higher for a long enough period.

The framing of the Kahneman and Tversky’s questions is no different than the framing of political and economic issues by the various media outlets (see Pessimism Porn). Fear can generate advertising revenue and fear can also push investors into paralysis (see the equity fund flow data in Fund Flows Paradox).

Greed can sell in the financial markets too. The main sources of financial market greed have been primarily limited to bonds, cash, and gold. If you caught those trends early enough, you are happy as a clam, but like most things in life, nothing lasts forever. The same principle applies to financial markets, and over time, capital in today’s winners will slowly transition into today’s losers (i.e., tomorrow’s winners).

A healthy amount of fear is healthy, but correctly understanding the dynamics of the “Pleasure/Pain Principle” can turn those fearful tears into profitable pleasure.

Wade W. Slome, CFA, CFP®

Plan. Invest. Prosper.

DISCLOSURE: Sidoxia Capital Management (SCM) and some of its clients own certain exchange traded funds (including fixed income ETFs), but at the time of publishing SCM had no direct position in GLD, or any other security referenced in this article. No information accessed through the Investing Caffeine (IC) website constitutes investment, financial, legal, tax or other advice nor is to be relied on in making an investment or other decision. Please read disclosure language on IC “Contact” page.

Alligators, Airplane Crashes, and the Investment Brain

“Neither a man nor a crowd nor a nation can be trusted to act humanely or think sanely under the influence of a great fear…To conquer fear is the beginning of wisdom.” – Bertrand Russell

Fear is a powerful force, and if not harnessed appropriately can prove ruinous and destructive to the performance of your investment portfolios. The preceding three years have shown the poisonous impacts fear can play on the average investor results, and Jason Zweig, financial columnist at The Wall Street Journal presciently wrote about this subject aptly titled “Fear,” just before the 2008 collapse.

Fear affects us all to differing degrees, and as Zweig points out, often this fear is misguided – even for professional investors. Zweig uses the advancements in neuroscience and behavioral finance to help explain how irrational decisions can often be made. To illustrate the folly in human’s thought process, Zweig offers up a multiple examples. Here is part of a questionnaire he highlights in his article:

“Which animal is responsible for the greatest number of human deaths in the U.S.?

A.) Alligator; B.) Bear; C.) Deer; D.) Shark; and E.) Snake

The ANSWER: C) Deer.

The seemingly most docile creature of the bunch turns out to cause the most deaths. Deer don’t attack with their teeth, but as it turns out, deer prance in front of speeding cars relatively frequently, thereby causing deadly collisions. In fact, deer collisions trigger seven times more deaths than alligators, bears, sharks, and snakes combined, according to Zweig.

Another factoid Zweig uses to explain cloudy human thought processes is the fear-filled topic of plane crashes versus car crashes. People feel very confident driving in a car, yet Zweig points out, you are 65 times more likely to get killed in your own car versus a plane, if you adjust for distance traveled. Hall of Fame NFL football coach John Madden hasn’t flown on an airplane since 1979 due to his fear of flying – investors make equally, if not more, irrational judgments in the investment world.

Professor Dr. Paul Slovic believes controllability and “knowability” contribute to the level of fear or perception of risk. Handguns are believed to be riskier than smoking, in large part because people do not have control over someone going on a gun rampage (i.e., Jared Loughner Tuscon, Arizona murders), while smokers have the power to just stop. The reality is smoking is much riskier than guns. On the “knowability” front, Zweig uses the tornadoes versus asthma comparison. Even though asthma kills more people, since it is silent and slow progressing, people generally believe tornadoes are riskier.

The Tangible Cause

Deep within the brain are two tiny, almond-shaped tissue formations called the amygdala. These parts of the brain, which have been in existence since the period of early-man, serve as an alarm system, which effectively functions as a fear reflex. For instance, the amygdala may elicit an instinctual body response if you encounter a bear, snake, or knife thrown at you.

Money fears set off the amygdala too. Zweig explains the linkage between fiscal and physical fears by stating, “Losing money can ignite the same fundamental fears you would feel if you encountered a charging tiger, got caught in a burning forest, or stood on the crumbling edge of a cliff.” Money plays such a large role in our society and can influence people’s psyches dramatically. Neuroscientist Antonio Damasio observed, “Money represents the means of maintaining life and sustaining us as organisms in our world.”

The Solutions

So as we deal with events such as the Lehman bankruptcy, flash crashes, Greek civil unrest, and Middle East political instability, how should investors cope with these intimidating fears? Zweig has a few recommended techniques to deal with this paramount problem:

1) Create a Distraction: When feeling stressed or overwhelmed by risk, Zweig urges investors to create a distraction or moment of brevity. He adds, “To break your anxiety, go for a walk, hit the gym, call a friend, play with your kids.”

2) Use Your Words: Objectively talking your way through a fearful investment situation can help prevent knee-jerk reactions and suboptimal outcomes. Zweig advises to the investor to answer a list of unbiased questions that forces the individual to focus on the facts – not the emotions.

3) Track Your Feelings: Many investors tend to become overenthusiastic near market tops and show despair near market bottoms. Long-term successful investors realize good investments usually make you sweat. Fidelity fund manager Brian Posner rightly stated, “If it makes me feel like I want to throw up, I can be pretty sure it’s a great investment.” Accomplished value fund manager Chris Davis echoed similar sentiments when he said, “We like the prices that pessimism produces.”

4) Get Away from the Herd: The best investment returns are not achieved by following the crowd. Get a broad range of opinions and continually test your investment thesis to make sure peer pressure is not driving key investment decisions.

Investors can become their worst enemies. Often these fears are created in our minds, whether self-inflicted or indirectly through the media or other source. Do yourself a favor and remove as much emotion from the investment decision-making process, so you do not become hostage to the fear du jour. Worrying too much about alligators and plane crashes will do more harm than good, when making critical decisions.

Read Other Jason Zweig Article from IC

Wade W. Slome, CFA, CFP®

Plan. Invest. Prosper.

DISCLOSURE: Sidoxia Capital Management (SCM) and some of its clients own certain exchange traded funds, but at the time of publishing SCM had no direct position in any other security referenced in this article. No information accessed through the Investing Caffeine (IC) website constitutes investment, financial, legal, tax or other advice nor is to be relied on in making an investment or other decision. Please read disclosure language on IC “Contact” page.

Crisis Delivers Black-Eye to Classic Economists

Markets are efficient. Individuals behave rationally. All information is reflected in prices. Huh…are you kidding me? These are the beliefs held by traditional free market economists (“rationalists”) like Eugene Fama (Economist at the University of Chicago and a.k.a. the “Father of the Efficient Market Hypothesis”). Striking blows to the rationalists are being thrown by “behavioralists” like Richard Thaler (Professor of Behavioral Science and Economics at the University of Chicago), who believes emotions often lead to suboptimal decisions and also thinks efficient market economics is a bunch of hogwash.

Individual investors, pensions, endowments, institutional investors, governments, are still sifting through the rubble in the aftermath of the 2008-2009 financial crisis. Experts and non-experts are still attempting to figure out how this mass destruction occurred and how it can be prevented in the future. Economists, as always, are happy to throw in their two cents. Right now traditional free market economists like Fama have received a black eye and are on the defensive – forced to explain to the behavioral finance economists (Thaler et. al.) how efficient markets could lead to such a disastrous outcome.

Religion and Economics

Like religious debates, economic rhetoric can get heated too. Religion can be divided up in into various categories (e.g., Christianity, Islam, Judaism, Hinduism, Buddhism, and other), or more simply religion can be divided into those who believe in a god (theism) and those who do not (atheism). There are multiple economic categorizations or schools as well (e.g., Keynsians, monetarism, libertarian, behavioral finance, etc.). Debates and disagreements across the rainbow of religions and economic schools have been going on for centuries, and the completion of the 2008-09 financial crisis has further ignited the battle between the “behavioralists” (behavioral finance economists) and the “rationalists” (traditional free market economists).

Behavioral Finance on the Offensive

In the efficient market world of the “rationalists,” market prices reflect all available information and cannot be wrong at any moment in time. Effectively, individuals are considered human calculators that optimize everything from interest rates and costs to benefits and inflation expectations in every decision. What classic economics does not include is emotions or behavioral flaws.

Purporting that financial market decisions are not impacted by emotions becomes more difficult to defend if you consider the countless irrational anomalies considered throughout history. Consider the following:

- Tulip Mania: Bubbles are nothing new – they have persisted for hundreds of years. Let’s reflect on the tulip bulb mania of the 1600s. For starters, I’m not sure how classic economists can explain the irrational exchanging of homes or a thousand pounds of cheese for a tulip bulb? Or how peak prices of $60,000+ in inflation-adjusted dollars were paid for a bulb at the time (C-Cynical)? These are tough questions to answer for the rationalists.

- Flash Crash: Seeing multiple stocks (i.e., ACN and EXC) and Exchange Traded Funds (ETFs) temporarily trade down -99% in minutes is not exactly efficient. Stalwarts like Procter & Gamble also collapsed -37%, only to rebound minutes later near pre-collapse levels. All this volatility doesn’t exactly ooze with efficiency (see Making Millions in Minutes).

- Negative T-Bill Rates: For certain periods of 2008 and 2009, investors earned negative yields on Treasury Bills. In essence, investors were paying the government to hold their money. Hmmm?

- Technology and Real Estate Bubbles: Both of these asset classes were considered “can’t lose” investments in the late 1990s and mid-2000s, respectively. Many tech stocks were trading at unfathomable values (more than 100 x’s annual profits) and homebuyers were inflating real estate prices because little to no money was required for the purchases.

- ’87 Crash: October 19, 1987 became infamously known as “Black Monday” since the Dow Jones Industrial Average plunged over -22% in one day (-508 points), the largest one-day percentage decline ever.

The list has the potential of going on forever, and the recent 2008-09 financial crisis only makes rationalists’ jobs tougher in refuting all this irrational behavior. Maybe the rationalists can use the same efficient market framework to help explain to my wife why I ate a whole box of Twinkies in one sitting?

Rationalist Rebuttal

The rationalists may have gotten a black eye, but they are not going down without a fight. Here are some quotes from Fama and fellow Chicago rationalist pals:

On the Crash-Related Attacks from Behavioralists: Behavioralists say traditional economics has failed in explaining the irrational decisions and actions leading up to the 2008-09 crash. Fama states, “I don’t see this as a failure of economics, but we need a whipping boy, and economists have always, kind of, been whipping boys, so they’re used to it. It’s fine.”

Rationalist Explanation of Behavioral Finance: Fama doesn’t deny the existence of irrational behavior, but rather believes rational and irrational behaviors can coexist. “Efficient markets can exist side by side with irrational behavior, as long as you have enough rational people to keep prices in line,” notes Fama. John Cochrane treats behavioral finance as a pseudo-science by replying, “The observation that people feel emotions means nothing. And if you’re going to just say markets went up because there was a wave of emotion, you’ve got nothing. That doesn’t tell us what circumstances are likely to make markets go up or down. That would not be a scientific theory.”

Description of Panics: “Panic” is not a term included in the dictionary of traditional economists. Fama retorts, “You can give it the charged word ‘panic,’ if you’d like, but in my view it’s just a change in tastes.” Calling these anomalous historic collapses a “change in tastes” is like calling Simon Cowell, formerly a judge on American Idol, “diplomatic.” More likely what’s really happening is these severe panics are driving investors’ changes in preferences.

Throwing in White Towel Regarding Crash: Not all classic economists are completely digging in their heels like Fama and Cochrane. Gary Becker, a rationalist disciple, acknowledges “Economists as a whole didn’t see it coming. So that’s a black mark on economics, and it’s not a very good mark for markets.”

Settling Dispute with Lab Rats

The boxing match continues, and the way the behavioralists would like to settle the score is through laboratory tests. In the documentary Mind Over Money, numerous laboratory experiments are run using human subjects to tease out emotional behaviors. Here are a few examples used by behavioralists to bolster their arguments:

- The $20 Bill Auction: Zach Burns, a professor at the University of Chicago, conducted an auction among his students for a $20 bill. Under the rules of the game, as expected, the highest bidder wins the $20 bill, but as an added wrinkle, Burns added the stipulation that the second highest bidder receives nothing but must still pay the amount of the losing bid. Traditional economists would conclude nobody would bid higher than $20. See the not-so rational auction results here at minute 1:45.

- $100 Today or $102 Tomorrow? This was the question posed to a group of shoppers in Chicago, but under two different scenarios. Under the first scenario, the individuals were asked whether they would prefer receiving $100 in a year from now (day 366) or $102 in a year and one additional day (day 367)? Under the second scenario, the individuals were asked whether they would prefer receiving $100 today or $102 tomorrow? The rational response to both scenarios would be to select $102 under both scenarios. See how the participants responded to the questions here at minute 4:30.

Rationalist John Cochrane is not fully convinced. “These experiments are very interesting, and I find them interesting, too. The next question is, to what extent does what we find in the lab translate into how people…understanding how people behave in the real world…and then make that transition to, ‘Does this explain market-wide phenomenon?,’” he asks.

As alluded to earlier, religion, politics, and economics will never fall under one universal consensus view. The classic rationalist economists, like Eugene Fama, have in aggregate been on the defensive and taken a left-hook in the eye for failing to predict and cohesively explain the financial crash of 2008-09. On the other hand, Richard Thaler and his behavioral finance buds will continue on the offensive, consistently swinging at the classic economists over this key economic mind versus money dispute.

See Complete Mind Over Money Program

Wade W. Slome, CFA, CFP®

Plan. Invest. Prosper.

DISCLOSURE: Sidoxia Capital Management (SCM) and some of its clients own certain exchange traded funds, but at the time of publishing SCM had no direct position in ACN, EXC, or any other security referenced in this article. No information accessed through the Investing Caffeine (IC) website constitutes investment, financial, legal, tax or other advice nor is to be relied on in making an investment or other decision. Please read disclosure language on IC “Contact” page.

Mauboussin Takes the Outside View

Michael Mauboussin, Legg Mason Chief Investment Strategist and author of Think Twice, is a behavioral finance guru and in his recent book he explores the importance of seriously considering the “outside view” when making important decisions.

What is Behavioral Finance?

Behavioral finance is a branch of economics that delves into the non-numeric forces impacting a diverse set of economic and investment decisions. Often these internal and external influences can lead to sub-optimal decision making. The study of this psychology-based discipline is designed to mitigate economic errors, and if possible, improve investment decision making.

Two instrumental contributors to the field of behavioral finance are economists Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky. In one area of their research they demonstrated how emotional fears of loss can have a crippling effect in the decision making process. In their studies, Kahneman and Tversky showed the pain of loss is more than twice as painful as the pleasure from gain. How did they illustrate this phenomenon? Through various hypothetical gambling scenarios, they highlighted how irrational decisions are made. For example, Kahneman and Tversky conducted an experiment in which participating individuals were given the choice of starting with an initial $600 nest egg that grows by $200, or beginning with $1,000 and losing $200. Both scenarios created the exact same end point ($800), but the participants overwhelmingly selected the first option (starting with lower $600 and achieving a gain) because starting with a higher value and subsequently losing money was not as comfortable.

The impression of behavioral finance is burned into our history in the form of cyclical boom, busts, and bubbles. Most individuals are aware of the technology bubble of the late 1990s, or the more recent real estate/credit craze, however investors tend to have short memories are unaware of previous behavioral bubbles. Take the 17th century tulip mania, which witnessed Dutch citizens selling land, homes, and other assets in order to procure tulip bulbs for more than $70,000 (on an inflation-adjusted basis), according to Stock-Market-Crash.net. We can attempt to delay bubbles, but they will forever be a part of our economic fabric.

The Outside View

Click here for Michael Mauboussin interview with Morningstar

Click here for Michael Mauboussin interview with Morningstar

In his book Think Twice Mauboussin takes tenets from behavioral finance and applies it to individual’s decision making process. Specifically, he encourages people to consider the “outside view” when making important decisions.

Mauboussin makes the case that our decisions are unique, but share aspects of other problems. Often individuals get trapped in their heads and internalize their own problems as part of the decision making process. Since decisions are usually made from our personal research and experiences, Mauboussin argues the end judgment is usually biased too optimistically. Mauboussin encourages decision makers to access a larger outside reference class of diverse opinions and historical situations. Often, situations and problems encountered by an individual have happened many times before and there is a “database of humanity” that can be tapped for improved decision making purposes. By taking the “outside view,” he believes individual judgments will be tempered and a more realistic perspective can be achieved.

In his interview with Morningstar, Mauboussin provides a few historical examples in making his point. He uses a conversation with a Wall Street analyst regarding Amazon (AMZN) to illustrate. This particular analyst said he was forecasting Amazon’s revenue growth to average 25% annually for the next ten years. Mauboussin chose to penetrate the “database of humanity” and ask the analyst how many companies in history have been able to sustainably grow at these growth rates? The answer… zero or only one company in history has been able to achieve a level of growth for that long, meaning the analyst’s projection is likely too optimistic.

Mean reversion is another concept Mauboussin addresses in his book. I consider mean reversion to be one of the most powerful principles in finance. This is the idea that upward or downward moving trends tend to revert back to an average or normal level over time. In describing this occurrence he directs attention to the currently, overly pessimistic sentiment in the equity markets (see also Pessimism Porn article). At end of 1999 people were wildly optimistic about the previous decade due to the significantly above trend-line returns earned. Mean reversion kicked in and the subsequent ten years generated significantly below-average returns. Fast forward to today and now the pendulum has swung to the other end. Investors are presently overly pessimistic regarding equity market prospects after experiencing a decade of below trend-line returns (simply look at the massive divergence in flows into bonds over stocks). Mauboussin, and I concur, come to the conclusion that equity markets are likely positioned to perform much better over the next decade relative to the last, thanks in large part to mean reversion.

Behavioral finance acknowledges one sleek, unique formula cannot create a solution for every problem. Investing includes a range of social, cognitive and emotional factors that can contribute to suboptimal decisions. Taking an “outside view” and becoming more aware of these psychological pitfalls may mitigate errors and improve decisions.

Wade W. Slome, CFA, CFP®

Plan. Invest. Prosper.

DISCLOSURE: Sidoxia Capital Management (SCM) and some of its clients own certain exchange traded funds and AMZN, but at time of publishing had no direct positions in LM, or MORN. No information accessed through the Investing Caffeine (IC) website constitutes investment, financial, legal, tax or other advice nor is to be relied on in making an investment or other decision. Please read disclosure language on IC “Contact” page.