Posts tagged ‘Myron Scholes’

Predictions – A Fool’s Errand

Making bold predictions is a fool’s errand. I think Yogi Berra summed it up best when he spoke about the challenges of making predictions:

“It’s tough to make predictions, especially about the future.”

While making predictions might seem like a pleasurable endeavor, the reality is nobody has been able to consistently predict the future (remember the 2012 Mayan Doomsday?), besides perhaps palm readers and Nostradamus. The typical observed pattern consists of a group of well-known forecasters bunched in a herd coupled with a few extreme outliers who try to make a big splash and draw attention to themselves. Due to the law of large numbers, a few of these extreme outlier forecasters eventually strike gold and become Wall Street darlings…until their next forecasts fail miserably.

Like a broken clock, these radical forecasters can be right twice per day but are wrong most of the time. Here are a few examples:

Peter Schiff: The former stockbroker and President of Euro Pacific Capital has been peddling doom for decades (see Emperor Schiff Has No Clothes). You can get a sense of his impartial perspective via Schiff’s reading list (The Real Crash: America’s Coming Bankruptcy, Financial Armageddon, Conquer the Crash, Crash Proof – America’s Great Depression, The Biggest Con: How the Government is Fleecing You, Manias Panics and Crashes, Meltdown, Greenspan’s Bubbles, The Dollar Crisis, America’s Bubble Economy, and other doom-instilled titles.

Meredith Whitney: She made an incredible bearish call on Citigroup Inc. (C) during the fall of 2007, alongside her accurate call of Citi’s dividend suspension. Unfortunately, her subsequent bearish calls on the municipal market and the stock market were completely wrong (see also Meredith Whitney’s Cloudy Crystal Ball).

John Mauldin: This former print shop professional turned perma-bear investment strategist has built a living incorrectly calling for a stock market crash. Like perma-bears before him, he will eventually be right when the next recession hits, but unfortunately, the massive appreciation will have been missed. Any eventual temporary setback will likely pale in comparison to the lost gains from being out of the market. I profiled the false forecaster in my article, The Man Who Cries Bear.

Nouriel Roubini: This renowned New York University economist and professor is better known as “Dr. Doom” and as one of the people who predicted the housing bubble and 2008-2009 financial crisis. Like most of the perma-bears who preceded him, Dr. Doom remained too doom-ful as the stock market more than tripled from the 2009 lows (see also Pinning Down Roubini).

Alan Greenspan: The graveyard of erroneous forecasters is so large that a proper summary would require multiple books. However, a few more of my favorites include Federal Reserve Chairman Alan Greenspan’s infamous “Irrational Exuberance” speech in 1996 when he warned of a technology bubble. Although directionally correct, the NASDAQ index proceeded to more than triple in value (from about 1,300 to over 5,000) over the next three years. – today the NASDAQ is hovering around 6,100.

Robert Merton & Myron Scholes: As I chronicled in Investing Caffeine (see When Genius Failed), another doozy is the story of the Long Term Capital Management hedge fund, which was run in tandem with Nobel Prize winning economists, Robert Merton and Myron Scholes. What started as $1.3 billion fund in early 1994 managed to peak at around $140 billion before eventually crumbling to a capital level of less than $1 billion. Regrettably, becoming a Nobel Prize winner doesn’t make you a great predictor.

Words From the Wise

Rather than paying attention to crazy predictions by academics, economists, and strategists who in many cases have never invested a penny of outside investor money, ordinary investors would be better served by listening to steely investment veterans or proven prediction practitioners like Billy Beane (minority owner of the Oakland Athletics and subject of Michael Lewis’s book, Moneyball), who stated the following:

“The crime is not being unable to predict something. The crime is thinking that you are able to predict something.”

Other great quotes regarding the art of predictions, include these ones:

“I can’t recall ever once having seen the name of a market timer on Forbes‘ annual list of the richest people in the world. If it were truly possible to predict corrections, you’d think somebody would have made billions by doing it.”

-Peter Lynch

“Many more investors claim the ability to foresee the market’s direction than actually possess the ability. (I myself have not met a single one.) Those of us who know that we cannot accurately forecast security prices are well advised to consider value investing, a safe and successful strategy in all investment environments.”

–Seth Klarman

“No matter how much research you do, you can neither predict nor control the future.”

–John Templeton

“Stop trying to predict the direction of the stock market, the economy or the elections.”

–Warren Buffett

“In the business world, the rearview mirror is always clearer than the windshield.”

–Warren Buffett

In the global financial markets, Wall Street is littered with strategists and economists who have flamed out after brief bouts of fame. Celebrated author Mark Twain captured the essence of speculation when he properly identified, “There are two times in a man’s life when he should not speculate: when he can’t afford it and when he can.” Instead of attempting to predict the future, investors will avoid a fool’s errand by simply seizing opportunities as they present themselves in an ever-changing world.

Wade W. Slome, CFA, CFP®

Plan. Invest. Prosper.

DISCLOSURE: Sidoxia Capital Management (SCM) and some of its clients own certain exchange traded funds, but at the time of publishing SCM had no direct position in any other security referenced in this article. No information accessed through the Investing Caffeine (IC) website constitutes investment, financial, legal, tax or other advice nor is to be relied on in making an investment or other decision. Please read disclosure language on IC “Contact” page.

Investing in a World of Black Swans

In the world of modern finance, there has always been the search for the Holy Grail. Ever since the advent of computers, practitioners have looked to harness the power of computing and direct it towards the goal of producing endless profits. Today the buzz words being used across industries include, “AI – Artificial Intelligence,” “Machine Learning,” “Neural Networks,” and “Deep Learning.” Regrettably, nobody has found a silver bullet, but that hasn’t slowed down people from trying. Wall Street has an innate desire to try to turn the ultra-complex field of finance into a science, just as they do in the field of physics. Even banking stalwart JPMorgan Chase (JPM) and its renowned CEO/Chairman Jamie Dimon suffered billions in losses in the quest for infinite income, due in large part to their over-reliance on pseudo-science trading models.

Preceding JPM’s losses, James Montier of Grantham Mayo van Otterloo’s asset allocation team gave a keynote speech at a CFA Institute Annual Conference in Chicago, where he gave a prescient talk explaining why bad models were the root cause of the financial crisis. Montier noted these computer algorithms essentially underappreciate the number and severity of Black Swan events (low probability negative outcomes) and the models’ inability to accurately identify predictable surprises.

What are predictable surprises? Here’s what Montier had to say on the topic:

“Predictable surprises are really about situations where some people are aware of the problem. The problem gets worse over time and eventually explodes into crisis.”

When Dimon was made aware of the 2012 rogue trading activities, he strenuously denied the problem before reversing course and admitting to the dilemma. Unfortunately, many of these Wall Street firms and financial institutions use value-at-risk (VaR) models that are falsely based on the belief that past results will repeat themselves, and financial market returns are normally distributed. Those suppositions are not always true.

Another perfect example of a Black Swan created by a bad financial model is Long Term Capital Management (LTCM) – see also When Genius Failed. Robert Merton and Myron Scholes were world renowned Nobel Prize winners who single-handedly brought the global financial market to its knees in 1998 when LTCM lost $500 million in one day and required a $3.6 billion bailout from a consortium of banks. Their mathematical models worked for a while but did not fully account for trading environments with low liquidity (i.e., traders fleeing in panic) and outcomes that defied the historical correlations embedded in their computer algorithms. The “Flash Crash” of 2010, in which liquidity evaporated due to high-frequency traders temporarily jumping ship, is another illustration of computers wreaking havoc on the financial markets.

The problem with many of these models, even for the ones that work in the short-run, is that behavior and correlations are constantly changing. Therefore any strategy successfully reaping outsized profits in the near-term will eventually be discovered by other financial vultures and exploited away.

Another pundit with a firm hold on Wall Street financial models is David Leinweber, author of Nerds on Wall Street. As Leinweber points out, financial models become meaningless if the data is sliced and diced to form manipulated and nonsensical relationships. The data coming out can only be as good as the data going in – “garbage in, garbage out.”

In searching for the most absurd data possible to explain the returns of the S&P 500 index, Leinweiber discovered that butter production in Bangladesh was an excellent predictor of stock market returns, explaining 75% of the variation of historical returns. By tossing in U.S. cheese production and the total population of sheep in Bangladesh, Leinweber was able to mathematically “predict” past U.S. stock returns with 99% accuracy. To read more about other financial modeling absurdities, check out a previous Investing Caffeine article, Butter in Bangladesh.

Generally, investors want precision through math, but as famed investor Benjamin Graham noted more than 50 years ago, “Mathematics is ordinarily considered as producing precise, dependable results. But in the stock market, the more elaborate and obtuse the mathematics, the more uncertain and speculative the conclusions we draw therefrom. Whenever calculus is brought in, or higher algebra, you can take it as a warning signal that the operator is trying to substitute theory for experience.”

If these models are so bad, then why do so many people use them? Montier points to “intentional blindness,” the tendency to see what one expects to see, and “distorted incentives” (i.e., compensation structures rewarding improper or risky behavior).

Montier’s solution to dealing with these models is not to completely eradicate them, but rather recognize the numerous shortcomings of them and instead focus on the robustness of these models. Or in other words, be skeptical, know the limits of the models, and build portfolios to survive multiple different environments.

Investors seem to be discovering more financial Black Swans over the last few years in the form of events like the Lehman Brothers bankruptcy, Flash Crash, and Greek sovereign debt default. Rather than putting too much faith or dependence on bad financial models to identify or exploit Black Swan events, the over-reliance on these models may turn this rare breed of swans into a large bevy.

See Full Article on Montier: Failures of Modern Finance

Wade W. Slome, CFA, CFP®

Plan. Invest. Prosper.

DISCLOSURE: Sidoxia Capital Management (SCM) and some of its clients own JPM and certain exchange traded funds, but at the time of publishing SCM had no direct position in Lehman Brothers, or any other security referenced in this article. No information accessed through the Investing Caffeine (IC) website constitutes investment, financial, legal, tax or other advice nor is to be relied on in making an investment or other decision. Please read disclosure language on IC “Contact” page.

When Genius Failed

It has been a busy year between work, play, family, and of course the recent elections. My work responsibilities contain a wide-ranging number of facets, but in addition to research, client meetings, conference calls, conferences, trading, and other activities, I also attempt to squeeze in some leisure reading as well. While it’s sad but true that I find pleasure in reading SEC documents (10Ks and 10Qs), press releases, transcripts, corporate presentations, financial periodicals, and blogs, I finally did manage to also scratch When Genius Failed by Roger Lowenstein from my financial reading bucket list.

When Genius Failed chronicles the rise and fall of what was considered the best and largest global hedge fund, Long Term Capital Management (LTCM). The irony behind the collapse makes the story especially intriguing. Despite melding the brightest minds in finance, including two Nobel Prize winners, Robert Merton and Myron Scholes, the Greenwich, Connecticut hedge fund that started with $1.3 billion in early 1994 managed to peak at around $140 billion before eventually crumbling to ruin.

With the help of confidential internal memos, interviews with former partners and employees of LTCM, discussions with the Federal Reserve, and consultations with the six major banks involved in the rescue, Lowenstein provides the reader with a unique fly-on-the-wall perspective to this grand financial crisis.

There have certainly been plenty of well-written books recounting the 2008-2009 financial crisis (see my review on Too Big to Fail), but the sheer volume has burnt me out on the subject. With that in mind, I decided to go back in time to the period of 1993 – 1998, a point at the beginning of my professional career. Until LTCM’s walls began figuratively caving in and global markets declined by more than $1 trillion in value, LTCM was successful at maintaining a relatively low profile. The vast majority of Americans (99%) had never heard of the small group of bright individuals who started LTCM, until the fund’s ultimate collapse blanketed every newspaper headline and media outlet.

Key Characters

Meriwether: John W. Meriwether was a legendary trader at Salomon Brothers, where he started the Arbitrage Group in 1977 and built up a successful team during the 1980s. His illustrious career is profiled in Michael Lewis’s famed book, Liar’s Poker. Meriwether built his trading philosophy upon the idea that mispricings would eventually revert back to the mean or converge, and therefore shrewd opportunistic trading will result in gains, if patience is used. Another name for this strategy is called “arbitrage”. In sports terms, the traders of the LTCM fund were looking for inaccurate point spreads, which could then be exploited for profit opportunity. Prior to the launch of LTCM, in 1991 Meriwether was embroiled in the middle of a U.S. Treasury bid-rigging scheme when one of his traders Paul Mozer admitted to submitting false bids to gain unauthorized advantages in government-bond auctions. John Gutfreund, Salomon Brothers’ CEO was eventually forced to quit, and Salomon’s largest, famed shareholder Warren Buffett became interim CEO. Meriwether was slapped on the wrist with a suspension and fine, and although Buffett eventually took back Meriwether in a demoted role, ultimately the trader was viewed as tainted goods so he left to start LTCM in 1993.

LTCM Team: During 1993 Meriwether built his professional team at LTCM and he began this process by recruiting several key Salomon Brothers bond traders. Larry Hilibrand and Victor Haghani were two of the central players at the firm. Other important principals included Eric Rosenfeld, William Krasker, Greg Hawkins, Dick Leahy, Robert Shustak, James McEntee, and David W. Mullins Jr.

Nobel Prize Winners (Merton & Scholes): While Robert C. Merton was teaching at Harvard University and Myron S. Scholes at Stanford University, they decided to put their academic theory to the real-world test by instituting their financial equations with the other investing veterans at LTCM. Scholes and Merton were effectively godfathers of quantitative theory. If there ever were a Financial Engineering Hall of Fame, Merton and Scholes would be initial inductees. Author Lowenstein described the situation by saying, “Long-Term had the equivalent of Michael Jordan and Muhammad Ali on the same team.” Paradoxically, in 1997, right before the collapse of LTCM, Merton and Scholes would become Nobel Prize laureates in Economic Sciences for their work in developing the theory of how to price options.

The History:

Founded in 1993, Long-Term Management Capital was hailed as the most impressive hedge fund created in history. Near its peak, LTCM managed money for about 100 investors and employed 200 employees. LTCM’s primary strategy was to identify mispriced bonds and profit from a mean reversion strategy. In other words, as long as the overall security mispricings narrowed, rather than widened, then LTCM would stand to profit handsomely.

On an individual trade basis, profits from LTCM’s trades were relatively small, but the fund implemented thousands of trades and used vast amounts of leverage (borrowings) to expand the overall profits of the fund. Lowenstein ascribed the fund’s success to the following process:

“Leveraging its tiny margins like a high-volume grocer, sucking up nickel after nickel and multiplying the process a thousand times.”

Although LTCM implemented this strategy successfully in the early years of the fund, this premise finally collapsed like a house of falling cards in 1998. As is generally the case, hedge funds and other banking competitors came to understand and copy LTCM’s successful trading strategies. Towards the end of the fund’s life, Meriwether and the other fund partners were forced to experiment with less familiar strategies like merger arbitrage, pair trades, emerging markets, and equity investing. This diversification strategy was well intentioned, however by venturing into uncharted waters, the traders were taking on excessive risk (i.e., they were increasing the probability of permanent capital losses).

The Timeline

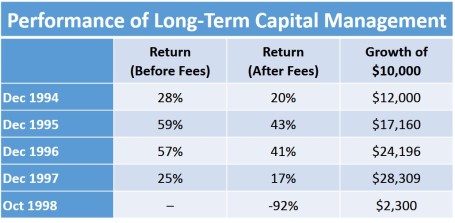

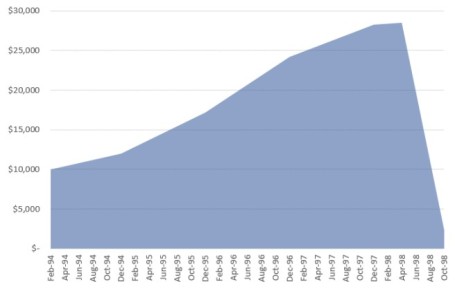

- 1994 (28% return, 20% after fees): After attempting to raise capital funding in 1993, LTCM opened its doors for business in February 1994 with $1.25 billion in equity. Financial markets were notably volatile during 1994 in part due to Federal Reserve Chairman Alan Greenspan leading the first interest rate hike in five years. The instability caused famed fund managers Michael Steinhardt and George Soros to lose -$800 million and $650 million, respectively, all within a timespan of less than a week. The so-called “Mexican Tequila Crisis” that occurred at the end of the year also resulted in a devaluation of the Mexican peso and crumbling of the Mexican stock market.

- 1995 (59% return, 43% after fees): By the end of 1995, the fund had tripled its equity capital and total assets had grown to $102 billion. Total leverage, or the ratio of debt to equity, stood around 28 to 1. LTCM’s derivative contract portfolio was like a powder keg, covering positions worth approximately $650 billion.

- 1996 (57% return, 41% after fees): By the spring of 1996, the fund was holding $140 billion in assets, making it two and a half times as big as Fidelity Magellan, the largest mutual fund on the planet. The fund also carried derivatives valued at more than $1 trillion, all financed off a relatively smaller $4 billion equity base. Investors were loving the returns and financial institutions were clamoring to gain some of LTCM’s business. During this period, as many as 55 banks were providing LTCM financing. The mega-returns earned in 1996 came in large part due to profitable leveraged spread trades on Japanese convertible bonds, Italian bonds, junk bonds, and interest rate swaps. Total profits for the year reached an extraordinary level of around $2.1 billion. To put that number in perspective, that figure was more money generated than the profits earned by McDonalds, Disney, American Express, Nike, Xerox, and many more Fortune 500 companies.

- 1997 (25% return, 17% after fees): The Asia Crisis came into full focus during October 1997. Thailand’s baht currency fell by -20% after the government decided to let the currency float freely. Currency weakness then spread to the Philippines, Malaysia, South Korea, and Singapore. As Russian bond spreads (prices) began to widen, massive trading losses for LTCM were beginning to compound. Returns remained positive for the year and the fund grew its equity capital to $5 billion. As the losses were mounting and the writing on the wall was revealing itself, professors Merton and Scholes were recognized with their Nobel Prize announcement. Ironically, LTCM was in the process of losing control. LTCM’s bloated number of 7,600 positions wasn’t making the fund any easier to manage. During 1997, the partners realized the fund’s foundation was shaky, so they returned $2.7 billion in capital to investors. Unfortunately, the risk profile of the fund worsened – not improved. More specifically, the fund’s leverage ratio skyrocketed from 18:1 to 28:1.

- 1998 (-92% return – loss): The Asian Crisis losses from the previous year began to bleed into added losses in 1998. In fact, losses during May and June alone ended up reducing LTCM’s capital by $461 million. As the losses racked up, LTCM was left in the unenviable position of unwinding a mind-boggling 60,000 individual positions. It goes almost without saying that selling is extraordinarily difficult during a panic. As Lowenstein put it, “Wall Street traders were running from Long-Term’s trades like rats from a sinking ship.” A few months later in September, LTCM’s capital shrunk to less than $1 billion, meaning about $100 billion in debt (leverage ratio greater than 100:1) was supporting the more than $100 billion in LTCM assets. It was just weeks later the fund collapsed abruptly. Russia defaulted on its ruble debt, and the collapsing currency contagion spread to global markets outside Russia, including Eastern Asia, and South America.

The End of LTCM

On September 23, 1998, after failed investment attempts by Warren Buffett and others to inject capital into LTCM, the heads of Bankers Trust, Bear Stearns, Chase Manhattan, Goldman Sachs, J.P. Morgan, Lehman Brothers, Merrill Lynch, Morgan Stanley Dean Witter, and Salomon Brothers all gathered at the Federal Reserve Bank of New York in the heart of Wall Street. Presiding over this historical get-together was Fed President, William J. McDonough. International markets were grinding to a halt during this period and the Fed was running out of time before an all-out meltdown was potentially about to occur. Ultimately, McDonough was able to get 14 banks to wire $3.65 billion in bailout funds to LTCM. While all LTCM partners were financially wiped out completely, initial investors managed to recoup a small portion of their original investment (23 cents on the dollar after factoring in fees), even though the tally of total losses reached approximately $4.6 billion. Once the bailout was complete, it took a few years for the fund to liquidate its gargantuan number of positions and for the banks to get their multi-billion dollar bailout paid back in full.

- 1999 – 2009 (Epilogue): Meriwether didn’t waste much time moping around after the LTCM collapse, so he started a new hedge fund, JWM Partners, with $250 million in seed capital primarily from legacy LTCM investors. Regrettably, the fund was hit with significant losses during the 2008-2009 Financial Crisis and was subsequently forced to close its doors in July 2009.

Source: The Personal Finance Engineer

Source: The Personal Finance Engineer

Lessons Learned:

- The Risks of Excessive Leverage: Although the fund grew to peak value of approximately $140 billion in assets, most of this growth was achieved with added debt. When all was said and done, LTCM borrowed more than 30 times the value of its equity. As Lowenstein put it, LTCM was “adding leverage to leverage, as if coating a flammable tinderbox with kerosene.” In home purchase terms, if LTCM wanted to buy a house using the same amount of debt as their fund, they would lose all of their investment, if the house value declined a mere 3-4%. The benefit of leverage is it multiplies gains. The downside to leverage is that it also multiplies losses. If you carry too much leverage in a declining market, the chance of bankruptcy rises…as the partners and investors of LTCM learned all too well. Adding fuel to the LTCM flames were the thousands of derivative contracts, valued at more than $1 trillion. Warren Buffett calls derivatives: “Weapons of Mass Destruction.”

- Past is Not Always Prologue for the Future: Just because a strategy works now or in the past, does not mean that same strategy will work in the future. As it relates to LTCM, Nobel Prize winning economist Merton Miller stated, “In a strict sense, there wasn’t any risk – if the world had behaved as it did in the past.” LTCM’s models worked for a while, then failed miserably. There is no Holy Grail investment strategy that works always. If an investment strategy sounds too good to be true, then it probably is too good to be true.

- Winning Strategies Eventually Get Competed Away: The spreads that LTCM looked to exploit became narrower over time. As the fund achieved significant excess returns, competitors copied the strategies. As spreads began to tighten even further, the only way LTCM could maintain their profits was by adding additional leverage (i.e., debt). High-frequency trading (HFT) is a modern example of this phenomenon, in which early players exploited a new technology-driven strategy, until copycats joined the fray to minimize the appeal by squeezing the pool of exploitable profits.

- Academics are Not Practitioners: Theory does not always translate into reality, and academics rarely perform as well as professional practitioners. Merton and Scholes figured this out the hard way. As Merton admitted after winning the Nobel Prize, “It’s a wrong perception to believe that you can eliminate risk just because you can measure it.”

- Size Matters: As new investors poured massive amounts of capital into the fund, the job of generating excess returns for LTCM managers became that much more difficult. I appreciate this lesson firsthand, given my professional experience in managing a $20 billion fund (see also Managing $20 Billion). Managing a massive fund is like maneuvering a supertanker – the larger a fund gets, the more difficult it becomes to react and anticipate market changes.

- Stick to Your Knitting: Because competitors caught onto their strategies, LTCM felt compelled to branch out. Meriwether and LTCM had an edge trading bonds but not in stocks. In the later innings of LTCM’s game, the firm became a big player in stocks. Not only did the firm place huge bets on merger arbitrage, but LTCM dabbled significantly in various long-short pair trades, including a $2.3 billion pair trade bet on Royal Dutch and Shell. Often the firm used derivative securities called equity swaps to make these trades without having to put up any significant capital. As LTCM experimented in the new world of equities, the firm was obviously playing in an area in which it had absolutely no expertise.

As philosopher George Santayana states, “Those who fail to learn from history are doomed to repeat it.” For those who take investing seriously, When Genius Failed is an important cautionary tale that provides many important lessons about financial markets and highlights the dangers of excessive leverage. You may not be a genius Nobel Prize winner in economics, but learning from Long-Term Capital Management’s failings will place you firmly on the path to becoming an investing genius.

Wade W. Slome, CFA, CFP®

Plan. Invest. Prosper.

DISCLOSURE: Sidoxia Capital Management (SCM) and some of its clients hold positions in certain exchange traded funds (ETFs), DIS, JPM, and MCD, but at the time of publishing had no direct position in AXP, NKE, XRX, RD, GS, MS, Shell, or any other security referenced in this article. No information accessed through the Investing Caffeine (IC) website constitutes investment, financial, legal, tax or other advice nor is to be relied on in making an investment or other decision. Please read disclosure language on IC Contact page

Yellen is “Yell-ing” About High Stock Prices!

Earlier this week, Janet Yellen, chair of the U.S. Federal Reserve, spoke at the Institute for New Economic Thinking conference at the IMF headquarters in Washington, D.C. In addition to pontificating about the state of the global economy and the direction of interest rates, she also decided to chime in with her two cents regarding the stock market by warning stock values are “quite high.” She went on to emphasize “there are potential dangers” in the equity markets.

Unfortunately, those investors who have hinged their investment careers on the forecasts of economists, strategists, and Fed Chairmen have suffered mightily. Already, Yellen’s soapbox rant about elevated stock prices is being compared to former Fed Chairman Alan Greenspan’s “Irrational Exuberance” speech, which I have previously discussed on numerous occasions (see Irrational Exuberance Déjà Vu).

Greenspan’s bubble warning talk was given on December 5, 1996 when the NASDAQ closed around 1,300 (it closed at 5,003 this week). Greenspan specifically said the following:

“But how do we know when irrational exuberance has unduly escalated asset values, which then become subject to unexpected and prolonged contractions as they have in Japan over the past decade?”

After his infamous speech, the NASDAQ index almost quadrupled in value to 5,132 in the ensuing three years before cratering by approximately -78%,

Greenspan’s successor, economics professor Ben Bernanke, didn’t fare much better than the previous Fed Chairmen. Unlike many, I give full credit where credit is due. Bernanke deserves extra credit for his nimble but aggressive actions that helped prevent a painful recession from expanding into a protracted and lethal depression.

With that said, as late as May 2007, Bernanke noted Fed officials “do not expect significant spillovers from the subprime market to the rest of the economy.” Moreover, in 2005, near the peak in housing prices, Bernanke said the probability of a housing bubble was “a pretty unlikely possibility.” Bernanke went on to add housing price increases, “largely reflect strong economic fundamentals.” Greenspan concurred with Bernanke. Just a year prior, Greenspan noted that the increase in home values was “not enough in our judgment to raise major concerns.” History has proven how Bernanke and Greenspan could not have been more wrong.

If you still believe Yellen is the bee’s knees when it comes to the investing prowess of economists, perhaps you should review Long Term Capital Management (LTCM) debacle. In the midst of the 1998 Asian financial crisis, Robert Merton and Myron Scholes, two world renowned Nobel Prize winners almost single handedly brought the global financial market to its knees. Merton and Scholes used their lifetime knowledge of economics to create complex computerized investment algorithms. Everything worked just fine until LTCM lost $500 million in one day, which required a $3.6 billion bailout from a consortium of banks.

NASDAQ 5,000…Bubble Repeat?

Janet Yellen’s recent prognostication about the valuation of the U.S. stock market happens to coincide with the NASDAQ index breaking through the 5,000 threshold, a feat not achieved since the piercing of the technology bubble in the year 2000. Investing Caffeine readers and investors of mine understand today’s NASDAQ index is much different than the NASDAQ index of 15 years ago (see also NASDAQ Redux), especially when it comes to valuation. The folks at Bespoke put NASDAQ 5,000 into an interesting context by adding the important factor of inflation to the mix. Even though the NASDAQ index is within spitting distance of its all-time high of 5,132 (reached in 2000), the index would actually need to rally another +40% to reach an all-time “inflation adjusted” closing high (see chart below).

Economists and strategists are usually articulate, and their arguments sound logical, but they are notorious for being horribly bad at predicting the future, Janet Yellen included. I agree valuation is an all-important factor in determining future stock market returns. Howeer, by Robert Shiller, Janet Yellen, and a host of other economists relying on one flawed metric (CAPE PE), they have not only been wildly wrong year after year, but they are recklessly neglecting many other key factors (see also Shiller CAPE Smells Like BS).

I freely admit stocks will eventually go down, most likely a garden variety -20% recessionary decline in prices. While from a historical standpoint we are overdue for another recession (about two recessions per decade), this recovery has been the slowest since World War II, and the yield curve is currently not flashing any warning signals. When the eventual stock market decline happens, it likely will not be driven by high valuations. The main culprit for a bear market will be a decline in earnings – high valuations just act as gasoline on the fire. Janet Yellen will continue to offer her opinions on many aspects of the economy, but if she steps on her soapbox again and yells about stock market valuations, you will be best served by purchasing a pair of earplugs.

Wade W. Slome, CFA, CFP®

Plan. Invest. Prosper.

DISCLOSURE: Sidoxia Capital Management (SCM) and some of its clients hold positions in certain exchange traded funds (ETFs), but at the time of publishing, SCM had no direct position in any other security referenced in this article. No information accessed through the Investing Caffeine (IC) website constitutes investment, financial, legal, tax or other advice nor is to be relied on in making an investment or other decision. Please read disclosure language on IC Contact page.

Investing in a World of Black Swans

In the world of modern finance, there has always been the search for the Holy Grail. Ever since the advent of computers, practitioners have looked to harness the power of computing and direct it towards the goal of producing endless profits. Regrettably, nobody has found the silver bullet, but that hasn’t slowed down people from trying. Wall Street has an innate desire to try to turn the ultra-complex field of finance into a science, just as they do in the field of physics. Even JPMorgan Chase (JPM) and its CEO Jamie Dimon are already on their way to suffering more than $2 billion in losses in the quest for infinite income, due in large part to their over-reliance on pseudo-science trading models.

James Montier of Grantham Mayo van Otterloo’s asset allocation team was recently a keynote speaker at the CFA Institute Annual Conference in Chicago. His prescient talk, which preceded JP Morgan’s recent speculative trading loss announcement, explained why bad models were the root cause of the financial crisis. Essentially these computer algorithms under-appreciate the number and severity of Black Swans (low probability negative outcomes) and the models’ inability to accurately identify predictable surprises.

What are predictable surprises? Here’s what Montier had to say on the topic:

“Predictable surprises are really about situations where some people are aware of the problem. The problem gets worse over time and eventually explodes into crisis.”

Just a month ago, when Dimon was made aware of the rogue trading activities, the CEO strenuously denied the problem before reversing course and admitting the dilemma last week. Unfortunately, many of these Wall Street firms and financial institutions use value-at-risk (VaR) models that are falsely based on the belief that past results will repeat themselves, and financial market returns are normally distributed. Those suppositions are not always true.

Another perfect example of a Black Swan created by a bad financial model is Long Term Capital Management (LTCM). Robert Merton and Myron Scholes were world renowned Nobel Prize winners who single handedly brought the global financial market to its knees in 1998 when LTCM lost $500 million in one day and required a $3.6 billion bailout from a consortium of banks. Their mathematical models worked for a while but did not fully account for trading environments with low liquidity (i.e., traders fleeing in panic) and outcomes that defied the historical correlations embedded in their computer algorithms. The “Flash Crash” of 2010, in which liquidity evaporated due to high frequency traders temporarily jumping ship, is another illustration of computers wreaking havoc on the financial markets.

The problem with many of these models, even for the ones that work in the short-run, is that behavior and correlations are constantly changing. Therefore any strategy successfully reaping outsized profits in the near-term will eventually be discovered by other financial vultures and exploited away.

Another pundit with a firm hold on Wall Street financial models is David Leinweber, author of Nerds on Wall Street. As Leinweber points out, financial models become meaningless if the data is sliced and diced to form manipulated and nonsensical relationships. The data coming out can only be as good as the data going in – “garbage in, garbage out.”

In searching for the most absurd data possible to explain the returns of the S&P 500 index, Leinweiber discovered that butter production in Bangladesh was an excellent predictor of stock market returns, explaining 75% of the variation of historical returns. By tossing in U.S. cheese production and the total population of sheep in Bangladesh, Leinweber was able to mathematically “predict” past U.S. stock returns with 99% accuracy. To read more about other financial modeling absurdities, check out a previous Investing Caffeine article, Butter in Bangladesh.

Generally, investors want precision through math, but as famed investor Benjamin Graham noted more than 50 years ago, “Mathematics is ordinarily considered as producing precise, dependable results. But in the stock market, the more elaborate and obtuse the mathematics, the more uncertain and speculative the conclusions we draw therefrom. Whenever calculus is brought in, or higher algebra, you can take it as a warning signal that the operator is trying to substitute theory for experience.”

If these models are so bad, then why do so many people use them? Montier points to “intentional blindness,” the tendency to see what one expects to see, and “distorted incentives” (i.e., compensation structures rewarding improper or risky behavior).

Montier’s solution to dealing with these models is not to completely eradicate them, but rather recognize the numerous shortcomings of them and instead focus on the robustness of these models. Or in other words, be skeptical, know the limits of the models, and build portfolios to survive multiple different environments.

Investors seem to be discovering more financial Black Swans over the last few years in the form of events like the Lehman Brothers bankruptcy, Flash Crash, and Greek sovereign debt default. Rather than putting too much faith or dependence on bad financial models to identify or exploit Black Swan events, the over-reliance on these models may turn this rare breed of swans into a large bevy.

See Full Article on Montier: Failures of Modern Finance

Wade W. Slome, CFA, CFP®

Plan. Invest. Prosper.

DISCLOSURE: Sidoxia Capital Management (SCM) and some of its clients own certain exchange traded funds, but at the time of publishing SCM had no direct position in JPM, Lehman Brothers, or any other security referenced in this article. No information accessed through the Investing Caffeine (IC) website constitutes investment, financial, legal, tax or other advice nor is to be relied on in making an investment or other decision. Please read disclosure language on IC “Contact” page.

Momentum Investing: Riding the Wave

As famed trader Jesse Livermore (July 26, 1877 — November 28, 1940) stated, “Prices are never too high to begin buying or too low to begin selling.”

For the most part, the momentum trading philosophy dovetails with Livermore’s mantra. The basic premise of momentum investing is to simply buy the outperforming stocks and sell (or short) the underperforming stocks. By following this rudimentary formula, investors can generate outsized returns. AQR Capital Management and Tobias Moskowitz (consultant), professor at Chicago Booth School of Management, ascribe to this belief too. AQR just recently launched the AQR Momentum Funds:

- AQR Momentum Fund (AMOMX – Domestic Large & Mid Cap)

- AQR Small Cap Momentum Fund (ASMOX – Domestic Small Cap)

- AQR International Momentum Fund (AIMOX – International Large & Mid Cap)

Professor Moskowitz Speaks on Bloomberg (Thought I looked young?!)

As I write in my book, How I Managed $20,000,000,000.00 by Age 32, I’m a big believer that successful investing requires a healthy mixture of both art and science. Too much of either will create negative outcomes. Modern finance teaches us that any profitable strategy will eventually be arbitraged away, such that any one profitable strategy will eventually stop producing profits.

A perfect example of a good strategy, gone bad is Long Term Capital Management. Robert Merton and Myron Scholes were world renowned Nobel Prize winners who single handedly brought the global financial markets to its knees in 1998 when it lost $500 million in one day and required a $3.6 billion bailout from a consortium of banks. Their mathematical models weren’t necessarily implementing momentum strategies, however this case is a good lesson in showing that even when smart people implement strategies that work for long periods of time, various factors can reverse the trend.

I wish AQR good luck with their quantitative momentum funds, but I hope they have a happier ending than Jesse Livermore. After making multiple fortunes and surviving multiple personal bankruptcies, Mr. Livermore committed suicide in 1940. In the mean time, surf’s up and the popularity of quantitative momentum funds remains alive and well.

Wade W. Slome, CFA, CFP®

Plan. Invest. Prosper.