Posts tagged ‘market efficiency’

A Recipe for Disaster

Justice does not always get served in the stock market because financial markets are not always efficient in the short-run (see Black-Eyes to Classic Economists). However, over the long-run, financial markets usually get it right. And when the laws of economics and physics are functioning properly, I must admit it, I do find it especially refreshing.

There can be numerous reasons for stocks to plummet in price, but common attributes to stock price declines often include profit losses and/or disproportionately high valuations (a.k.a. “bubbles”). Normally, your garden variety, recipe for disaster consists of one part highly valued company and one part money-losing operation (or deteriorating financials). The reverse holds true for a winning stock recipe. Flavorful results usually involve cheaply valued stocks paired with improving financial results.

Unfortunately, just because you have the proper recipe of investment ingredients, doesn’t mean you will immediately get to enjoy a satisfying feast. In other words, there isn’t a dinner bell rung to signal the timing of a crash or spike – sometimes there is a conspicuous catalyst and sometimes there is not. Frequently, investments require a longer expected bake time before the anticipated output is produced.

As I alluded to at the beginning of my post, justice is not always served immediately, but for some high profile IPOs, low-quality ingredients have indeed produced low-quality results.

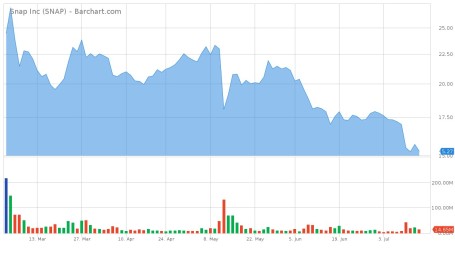

Snap Inc. (SNAP): Let’s first start with the high-flying social media darling Snap, which priced its IPO at $17 per share in March, earlier this year. How can a beloved social media company that generates $515 million in annual revenue (up +286% in the recent quarter) see its stock plummet -48% from its high of $29.44 to $15.27 in just four short months? Well, one way of achieving these dismal results is to burn through more cash than you’re generating in revenue. Snap actually scorched through more than -$745 million dollars over the last year, as the company reported accounting losses of -$618 million (excluding -$2 billion of stock-based compensation expenses). We’ll find out if the financial bleeding will eventually stop, but even after this year’s stock price crash, investors are still giving the company the benefit of the doubt by valuing the company at $18 billion today.

Source: Barchart.com

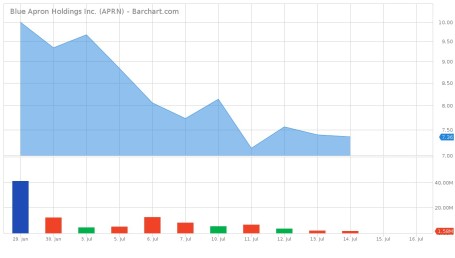

Blue Apron Holdings Inc. (APRN): Online meal delivery favorite, Blue Apron, is another company suffering from the post-IPO blues. After initially targeting an opening IPO price of $15-$17 per share a few weeks ago, tepid demand forced Blue Apron executives to cut the price to $10. Fast forward to today, and the stock closed at $7.36, down -26% from the IPO price, and -57% below the high-end of the originally planned range. Although the company isn’t hemorrhaging losses at the same absolute level of Snap, it’s not a pretty picture. Blue Apron has still managed to burn -$83 million of cash on $795 million in annual sales. Unlike Snap (high margin advertising revenues), Blue Apron will become a low-profit margin business, even if the company has the fortune of reaching high volume scale. Even after considering Blue Apron’s $1 billion annual revenue run rate, which is 50% greater than Snap’s $600 million run-rate, Blue Apron’s $1.4 billion market value is sadly less than 10% of Snap’s market value.

Source: Barchart.com

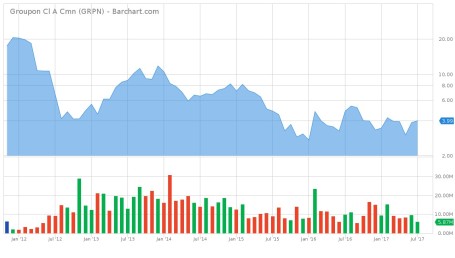

Groupon Inc. (GRPN): Unlike Snap and Blue Apron, Groupon also has the flattering distinction of reporting an accounting profit, albeit a small one. However, on a cash-based analysis, Groupon looks a little better than the previous two companies mentioned, if you consider an annual -$7 million cash burn “better”. Competition in the online discounting space has been fierce, and as such, Groupon has experienced a competitive haircut in its share price. Groupon’s original IPO price was $20 in January 2011 before briefly spiking to $31. Today, the stock has languished to $4 (-87% from the 2011 peak).

Source: Barchart.com

Stock Market Recipe?

Similar ingredients (i.e., valuations and profit trajectory) that apply to stock performance also apply to stock market performance. Despite record corporate profits (growing double digits), low unemployment, low inflation, low-interest rates, and a recovering global economy, bears and even rational observers have been worried about a looming market crash. Not only have the broader masses been worried today, yesterday, last week, last month, and last year, but they have also been worried for the last nine years. As I have documented repeatedly (see also Market Champagne Sits on Ice), the market has more than tripled to new record highs since early 2009, despite the strong under-current of endless cynicism.

Historically market tops have been marked by a period of excesses, including excessive emotions (i.e., euphoria). It has been a long time since the last recession, but economic downturns are also often marked with excessive leverage (e.g., housing in the mid-2000s), excessive capital (e.g., technology IPOs [Initial Public Offerings] in the late-1990s), and excessive investment (e.g., construction / manufacturing in early-1990s).

To date, we have seen little evidence of these markers. Certainly there have been pockets of excesses, including overpriced billion dollar tech unicorns (see Dying Unicorns), exorbitant commercial real estate prices, and a bubble in global sovereign debt, but on a broad basis, I have consistently said stocks are reasonably priced in light of record-low interest rates, a view also held by Warren Buffett.

The key lessons to learn, whether you are investing in individual stocks or the stock market more broadly, are that prices will follow the direction of earnings over the long-run. This helps explain why stock prices always go down in recessions (and are volatile in anticipation of recessions).

If you are looking for a recipe for disaster, just find an overpriced investment with money-losing (or deteriorating) characteristics. Avoiding these investments and identifying investments with cheap growth qualities is much easier said than done. However, by mixing an objective, quantitative framework with more artistic fundamental analysis, you will be in a position of enjoying tastier returns.

Wade W. Slome, CFA, CFP®

Plan. Invest. Prosper.

DISCLOSURE: Sidoxia Capital Management (SCM) and some of its clients hold positions in certain exchange traded funds (ETFs), but at the time of publishing, SCM had no direct position in SNAP, APRN, GRPN, or any other security referenced in this article. No information accessed through the Investing Caffeine (IC) website constitutes investment, financial, legal, tax or other advice nor is the information to be relied on in making an investment or other decision. Please read disclosure language on IC Contact page.

Munger: Buffett’s Wingman & the Art of Stock Picking

Simon had Garfunkel, Batman had Robin, Hall had Oates, Dr. Evil had Mini Me, Sonny had Cher, and Malone had Stockton. In the investing world, Buffett has Munger. Charlie Munger is one of the most successful and famous wingmen of all-time – evidenced by Berkshire Hathaway Corporation’s (BRKA/B) outperformance of the S&P 500 index by approximately +624% from 1977 – 2009, according to MarketWatch. Munger not only provides critical insights to his legendary billionaire boss, Warren Buffett, but he was also Chairman of Berkshire’s insurance subsidiary, Wesco Financial Corporation from 1984 until 2011. The magic of this dynamic duo began when they met at a dinner party 58 years ago (1959).

In an article he published in 2006, the magnificent Munger describes the “Art of Stock Picking” in a thorough review about the secrets of equity investing. We’ll now explore some of the 93-year-old’s sage advice and wisdom.

Model Building

Charlie Munger believes an individual needs a solid general education before becoming a successful investor, and in order to do that one needs to study and understand multiple “models.”

“You’ve got to have models in your head. And you’ve got to array your experience both vicarious and direct on this latticework of models. You may have noticed students who just try to remember and pound back what is remembered. Well, they fail in school and in life. You’ve got to hang experience on a latticework of models in your head.”

Although Munger indicates there are 80 or 90 important models, the examples he provides include mathematics, accounting, biology, physiology, psychology, and microeconomics.

Advantages of Scale

Great businesses in many cases enjoy the benefits of scale, and Munger devotes a good amount of time to this subject. Scale advantages can be realized through advertising, information, psychological “social proofing,” and structural factors.

The newspaper industry is an example of a structural scale business in which a “winner takes all” phenomenon applies. Munger aptly points out, “There’s practically no city left in the U.S., aside from a few very big ones, where there’s more than one daily newspaper.”

General Electric Co. (GE) is another example of a company that uses scale to its advantage. Jack Welch, the former General Electric CEO, learned an early lesson. If the GE division is not large enough to be a leader in a particular industry, then they should exit. Or as Welch put it, “To hell with it. We’re either going to be # 1 or #2 in every field we’re in or we’re going to be out. I don’t care how many people I have to fire and what I have to sell. We’re going to be #1 or #2 or out.”

Bigger Not Always Better

Scale comes with its advantages, but if not managed correctly, size can weigh on a company like an anchor. Munger highlights the tendency of large corporations to become “big, fat, dumb, unmotivated bureaucracies.” An implicit corruption also leads to “layers of management and associated costs that nobody needs. Then, while people are justifying all these layers, it takes forever to get anything done. They’re too slow to make decisions and nimbler people run circles around them.”

Becoming too large can also create group-think, or what Munger calls “Pavlovian Association.” Munger goes onto add, “If people tell you what you really don’t want to hear what’s unpleasant there’s an almost automatic reaction of antipathy…You can get severe malfunction in the high ranks of business. And of course, if you’re investing, it can make a lot of difference.”

Technology: Benefit or Burden?

Munger recognizes that technology lowers costs for companies, but the important question that many managers fail to ask themselves is whether the benefits from technology investments accrue to the company or to the customer? Munger summed it up here:

“There are all kinds of wonderful new inventions that give you nothing as owners except the opportunity to spend a lot more money in a business that’s still going to be lousy. The money still won’t come to you. All of the advantages from great improvements are going to flow through to the customers.”

Buffett and Munger realized this lesson early on when productivity improvements gained from technology investments in the textile business all went to the buyers.

Surfing the Wave

When looking for good businesses, Munger and Buffett are looking to “surf” waves or trends that will generate healthy returns for an extended period of time. “When a surfer gets up and catches the wave and just stays there, he can go a long, long time. But if he gets off the wave, he becomes mired in shallows,” states Munger. He notes that it’s the “early bird,” or company that identifies a big trend before others that enjoys the spoils. Examples Munger uses to illustrate this point are Microsoft Corp. (MSFT), Intel Corp. (INTC), and National Cash Register from the old days.

Large profits will be collected by those investors that can identify and surf those rare large waves. Unfortunately, taking advantage of these rare circumstances becomes tougher and tougher for larger investors like Berkshire. If you’re an elephant trying to surf a wave, you need to find larger and larger waves, and even then, due to your size, you will be unable to surf as long as small investors.

Circle of Competence

Circle of competence is not a new subject discussed by Buffett and Munger, but it is always worth reviewing. Here’s how Munger describes the concept:

“You have to figure out what your own aptitudes are. If you play games where other people have the aptitudes and you don’t, you’re going to lose. And that’s as close to certain as any prediction that you can make. You have to figure out where you’ve got an edge. And you’ve got to play within your own circle of competence.”

For Munger and Buffett, sticking to their circle of competence means staying away from high-technology companies, although more recently they have expanded this view to include International Business Machines (IBM), which they are now a large investor.

Market Efficiency or Lack Thereof

Munger acknowledges that financial markets are quite difficult to beat. Since the markets are “partly efficient and partly inefficient,” he believes there is a minority of individuals who can outperform the markets. To expand on this idea, he compares stock investing to the pari-mutuel system at the racetrack, which despite the odds stacked against the bettor (17% in fees going to the racetrack), there are a few individuals who can still make decent money.

The transactional costs are much lower for stocks, but success for an investor still requires discipline and patience. As Munger declares, “The way to win is to work, work, work, work and hope to have a few insights.”

Winning the Game – 10 Insights / 20 Punches

As the previous section implies, outperformance requires patience and a discriminating eye, which has allowed Berkshire to create the bulk of its wealth from a relatively small number of investment insights. Here’s Munger’s explanation on this matter:

“How many insights do you need? Well, I’d argue: that you don’t need many in a lifetime. If you look at Berkshire Hathaway and all of its accumulated billions, the top ten insights account for most of it….I don’t mean to say that [Warren] only had ten insights. I’m just saying, that most of the money came from ten insights.”

Chasing performance, trading too much, being too timid, and paying too high a price are not recipes for success. Independent thought accompanied with selective, bold decisions is the way to go. Munger’s solution to these problems is to provide investors with a Buffett 20-punch ticket:

“I could improve your ultimate financial welfare by giving you a ticket with only 20 slots in it so that you had 20 punches ‑ representing all the investments that you got to make in a lifetime. And once you’d punched through the card, you couldn’t make any more investments at all.”

The great thing about Munger and Buffett’s advice is that it is digestible by the masses. Like dieting, investing can be very simple to understand, but difficult to execute, and legends like these always remind us of the important investing basics. Even though Charlie Munger may be slowing down a tad at 93-years-old, Warren Buffett and investors everywhere are blessed to have this wingman around spreading his knowledge about investing and the art of stock picking.

Wade W. Slome, CFA, CFP®

Plan. Invest. Prosper.

DISCLOSURE: Sidoxia Capital Management (SCM) and some of its clients own certain exchange traded funds, BRKA/B, GE, MSFT, INTC, IBM but at the time of this 3/12/17 updated publishing, SCM had no direct position in National Cash Register, or any other security referenced in this article. No information accessed through the Investing Caffeine (IC) website constitutes investment, financial, legal, tax or other advice nor is to be relied on in making an investment or other decision. Please read disclosure language on IC “Contact” page.

Munger: Buffett’s Wingman & the Art of Stock Picking

Simon had Garfunkel, Batman had Robin, Hall had Oates, Dr. Evil had Mini Me, Sonny had Cher, and Malone had Stockton. In the investing world, Buffett has Munger. Charlie Munger is one of the most successful and famous wingmen of all-time – evidenced by Berkshire Hathaway Corporation’s (BRKA/B) outperformance of the S&P 500 index by approximately +624% from 1977 – 2009, according to MarketWatch. Munger not only provides critical insights to his legendary billionaire boss, Warren Buffett, but he also is Chairman of Berkshire’s insurance subsidiary, Wesco Financial Corporation. The magic of this dynamic duo began when they met at a dinner party during 1959.

In an article he published in 2006, the magnificent Munger describes the “Art of Stock Picking” in a thorough review about the secrets of equity investing. We’ll now explore some of the 88-year-old’s sage advice and wisdom.

Model Building

Charlie Munger believes an individual needs a solid general education before becoming a successful investor, and in order to do that one needs to study and understand multiple “models.”

“You’ve got to have models in your head. And you’ve got to array your experience both vicarious and direct on this latticework of models. You may have noticed students who just try to remember and pound back what is remembered. Well, they fail in school and in life. You’ve got to hang experience on a latticework of models in your head.”

Although Munger indicates there are 80 or 90 important models, the examples he provides include mathematics, accounting, biology, physiology, psychology, and microeconomics.

Advantages of Scale

Great businesses in many cases enjoy the benefits of scale, and Munger devotes a good amount of time to this subject. Scale advantages can be realized through advertising, information, psychological “social proofing,” and structural factors.

The newspaper industry is an example of a structural scale business in which a “winner takes all” phenomenon applies. Munger aptly points out, “There’s practically no city left in the U.S., aside from a few very big ones, where there’s more than one daily newspaper.”

General Electric Co. (GE) is another example of a company that uses scale to its advantage. Jack Welch, the former General Electric CEO, learned an early lesson. If the GE division is not large enough to be a leader in a particular industry, then they should exit. Or as Welch put it, “To hell with it. We’re either going to be # 1 or #2 in every field we’re in or we’re going to be out. I don’t care how many people I have to fire and what I have to sell. We’re going to be #I or #2 or out.”

Bigger Not Always Better

Scale comes with its advantages, but if not managed correctly, size can weigh on a company like an anchor. Munger highlights the tendency of large corporations to become “big, fat, dumb, unmotivated bureaucracies.” An implicit corruption also leads to “layers of management and associated costs that nobody needs. Then, while people are justifying all these layers, it takes forever to get anything done. They’re too slow to make decisions and nimbler people run circles around them.”

Becoming too large can also create group-think, or what Munger calls “Pavlovian Association.” Munger goes onto add, “If people tell you what you really don’t want to hear what’s unpleasant there’s an almost automatic reaction of antipathy…You can get severe malfunction in the high ranks of business. And of course, if you’re investing, it can make a lot of difference.”

Technology: Benefit or Burden?

Munger recognizes that technology lowers costs for companies, but the important question that many managers fail to ask themselves is whether the benefits from technology investments accrue to the company or to the customer? Munger summed it up here:

“There are all kinds of wonderful new inventions that give you nothing as owners except the opportunity to spend a lot more money in a business that’s still going to be lousy. The money still won’t come to you. All of the advantages from great improvements are going to flow through to the customers.”

Buffett and Munger realized this lesson early on when productivity improvements gained from technology investments in the textile business all went to the buyers.

Surfing the Wave

When looking for good businesses, Munger and Buffett are looking to “surf” waves or trends that will generate healthy returns for an extended period of time. “When a surfer gets up and catches the wave and just stays there, he can go a long, long time. But if he gets off the wave, he becomes mired in shallows,” states Munger. He notes that it’s the “early bird,” or company that identifies a big trend before others that enjoys the spoils. Examples Munger uses to illustrate this point are Microsoft Corp. (MSFT), Intel Corp. (INTC), and National Cash Register from the old days.

Large profits will be collected by those investors that can identify and surf those rare large waves. Unfortunately, taking advantage of these rare circumstances becomes tougher and tougher for larger investors like Berkshire. If you’re an elephant trying to surf a wave, you need to find larger and larger waves, and even then, due to your size, you will be unable to surf as long as small investors.

Circle of Competence

Circle of competence is not a new subject discussed by Buffett and Munger, but it is always worth reviewing. Here’s how Munger describes the concept:

“You have to figure out what your own aptitudes are. If you play games where other people have the aptitudes and you don’t, you’re going to lose. And that’s as close to certain as any prediction that you can make. You have to figure out where you’ve got an edge. And you’ve got to play within your own circle of competence.”

For Munger and Buffett, sticking to their circle of competence means staying away from high-technology companies, although more recently they have expanded this view to include International Business Machines (IBM), which they invested in late last year.

Market Efficiency or Lack Thereof

Munger acknowledges that financial markets are quite difficult to beat. Since the markets are “partly efficient and partly inefficient,” he believes there is a minority of individuals who can outperform the markets. To expand on this idea, he compares stock investing to the pari-mutuel system at the racetrack, which despite the odds stacked against the bettor (17% in fees going to the racetrack), there are a few individuals who can still make decent money.

The transactional costs are much lower for stocks, but success for an investor still requires discipline and patience. As Munger declares, “The way to win is to work, work, work, work and hope to have a few insights.”

Winning the Game – 10 Insights / 20 Punches

As the previous section implies, outperformance requires patience and a discriminating eye, which has allowed Berkshire to create the bulk of its wealth from a relatively small number of investment insights. Here’s Munger’s explanation on this matter:

“How many insights do you need? Well, I’d argue: that you don’t need many in a lifetime. If you look at Berkshire Hathaway and all of its accumulated billions, the top ten insights account for most of it….I don’t mean to say that [Warren] only had ten insights. I’m just saying, that most of the money came from ten insights.”

Chasing performance, trading too much, being too timid, and paying too high a price are not recipes for success. Independent thought accompanied with selective, bold decisions is the way to go. Munger’s solution to these problems is to provide investors with a Buffett 20-punch ticket:

“I could improve your ultimate financial welfare by giving you a ticket with only 20 slots in it so that you had 20 punches ‑ representing all the investments that you got to make in a lifetime. And once you’d punched through the card, you couldn’t make any more investments at all.”

The great thing about Munger and Buffett’s advice is that it is digestible by the masses. Like dieting, investing can be very simple to understand, but difficult to execute, and legends like these always remind us of the important investing basics. Even though Charlie Munger may be slowing down a tad at 88-years-old, Warren Buffett and investors everywhere are blessed to have this wingman around spreading his knowledge about investing and the art of stock picking.

Wade W. Slome, CFA, CFP®

Plan. Invest. Prosper.

DISCLOSURE: Sidoxia Capital Management (SCM) and some of its clients own certain exchange traded funds, but at the time of publishing SCM had no direct position in BRKA/B, GE, MSFT, INTC, National Cash Register, IBM, or any other security referenced in this article. No information accessed through the Investing Caffeine (IC) website constitutes investment, financial, legal, tax or other advice nor is to be relied on in making an investment or other decision. Please read disclosure language on IC “Contact” page.