Posts tagged ‘economics’

Supply & Demand: The Key to Oil, Stocks, and Pork Bellies

Commodity prices, including oil, are “crashing” according to the pundits and fears are building that this is a precursor to another stock market collapse. Are we on an irreversible path of repeating the bloodbath carnage of the 2008-2009 Great Recession?

Fortunately for investors, markets move in cycles and the fundamental laws of supply and demand hold true in both bull and bear markets, across all financial markets. Whether we are talking about stocks, bonds, copper, gold, currencies, or pork bellies, markets persistently move like a pendulum through periods of excess supply and demand. In other words, weakness in prices create stronger demand and less supply, whereas strength in prices creates weakening demand and more supply.

Since energy makes the world go round and the vast majority of drivers are accustomed to filling up their gas tanks, the average consumer is familiar with recent negative price developments in the crude oil markets. Eighteenth-century economist Adam Smith would be proud that the laws of supply and demand have help up just as well today as they did when he wrote Wealth of Nations in 1776.

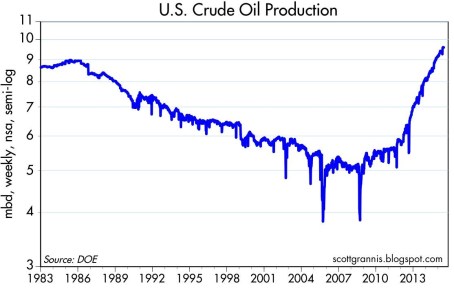

It is true that overall stagnation in global economic demand in recent years, along with the strengthening of the U.S. dollar (because of better relative growth), has contributed to downward trending oil prices. It is also true that supply factors, such as Saudi Arabia’s insistence to maintain production and the boom in U.S. oil production due to new fracking technologies (see chart below), have arguably had a larger negative impact on the more than -50% deterioration in oil prices. Fears of additional Iranian oil supply hitting the global oil markets as a result of the Iranian nuclear deal have also added to the downward pressure on prices.

What is bad for oil prices and the oil producers is good news for the rest of the economy. Transportation is the lubricant of the global economy, and therefore lower oil prices will act as a stimulant for large swaths of the global marketplace. Here in the U.S., consumer savings from lower energy prices have largely been used to pay down debt (deleverage), but eventually, the longer oil prices remain depressed, incremental savings should filter into our economy through increased consumer spending.

But prices are likely not going to stay low forever because producers are responding drastically to the price declines. All one needs to do is look at the radical falloff in the oil producer rig count (see chart below). As you can see, the rig count has fallen by more than -50% within a six month period, meaning at some point, the decline in global production will eventually provide a floor to prices and ultimately provide a tailwind.

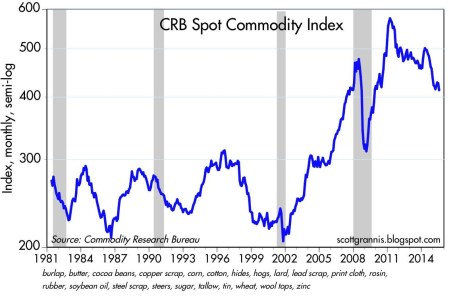

If we broaden our perspective beyond just oil, and look at the broader commodity complex, we can see that the recent decline in commodity prices has been painful, but nowhere near the Armageddon scenario experienced during 2008-2009 (see chart below – gray areas = recessions).

Although this conversation has focused on commodities, the same supply-demand principles apply to the stock market as well. Stock market prices as measured by the S&P 500 index have remained near record levels, but as I have written in the past, the records cannot be attributed to the lackluster demand from retail investors (see ICI fund flow data).

Although U.S. stock fundamentals remain relatively strong (e.g., earnings, interest rates, valuations, psychology), much of the strength can be explained by the constrained supply of stocks. How has stock supply been constrained? Some key factors include the trillions in dollars of supply soaked up by record M&A activity (mergers and acquisition) and share buybacks.

In addition to the declining stock supply from M&A and share buybacks, there has been limited supply of new IPO issues (initial public offerings) coming to market, as evidenced by the declines in IPO dollar and unit volumes in the first half of 2015, as compared to last year. More specifically, first half IPO dollar volmes were down -41% to $19.2 billion and the number of 2015 IPOs has declined -27% to 116 from 160 for the same time period.

Price cycles vary dramatically in price and duration across all financial markets, including stocks, bonds, oil, interest rates, currencies, gold, and pork bellies, among others. Not even the smartest individual or most powerful computer on the planet can consistently time the short-term shifts in financial markets, but using the powerful economic laws of supply and demand can help you profitably make adjustments to your investment portfolio(s).

See Also – The Lesson of a Lifetime (Investing Caffeine)

Wade W. Slome, CFA, CFP®

Plan. Invest. Prosper.

DISCLOSURE: Sidoxia Capital Management (SCM) and some of its clients hold positions in certain exchange traded funds (ETFs), but at the time of publishing, SCM had no direct position in any other security referenced in this article. No information accessed through the Investing Caffeine (IC) website constitutes investment, financial, legal, tax or other advice nor is to be relied on in making an investment or other decision. Please read disclosure language on IC Contact page.

Don’t Be a Fool, Follow the Stool

It’s the holiday season and with another year coming to an end, it’s also time for a wide range of religious celebrations to take place. Investing is a lot like religion too. Just like there are a countless number of religions, there are also a countless number of investing styles, whether you are talking about Value investing, Growth, Quantitative, Technical, Momentum, Merger-Arbitrage, GARP (Growth At a Reasonable Price), or a multitude of other derivative types. But regardless of the style followed, most professional managers believe their style is the sole answer to lead followers to financial nirvana. While I may not share the same view (I believe there are many ways to skin the stock market cat), each investing discipline (or religion) will have its own unique core tenets that drive expectations for future returns (outcomes).

As it relates to my firm, Sidoxia Capital Management, our investment process is premised on four key tenets. Much like the four legs of a stool, the following principles provide the foundation for our beliefs and outlook on the mid-to-long-term direction of the stock market:

- Profits

- Interest Rates

- Sentiment

- Valuations

Why are these the key components that drive stock market returns? Let’s dig a little deeper to clarify the importance of these factors:

Profits: Over the long-run there is a very significant correlation between stock prices and profits (see also It’s the Earnings, Stupid). I’m not the only one preaching this religious belief, investment legends Peter Lynch and William O’Neil think the same. In answer to a question by Dell Computer’s CEO Michael Dell about its stock price, Lynch famously responded , “If your earnings are higher in five years, your stock will be higher.” The same idea works with the overall stock market. As I recently wrote (see Why Buy at Record Highs? Ask the Fat Turkey), with corporate profits at all-time record highs, it should come as no surprise that stock prices are near all-time record highs. Regardless of the absolute level of profits, it’s also very important to have a feel for whether earnings are accelerating or decelerating, because investors will pay a different price based on this dynamic.

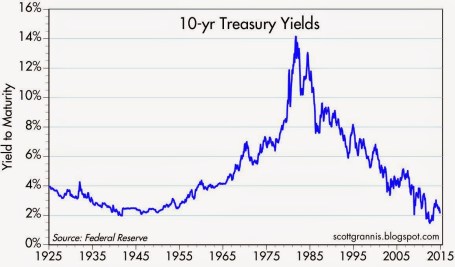

Interest Rates: When embarrassingly low CD interest rates of 0.08% are being offered on $10,000 deposits at Bank of America, do you think stocks look more or less attractive? It’s obviously a rhetorical question, because I can earn 20x more just by collecting the dividends from the S&P 500 index. Now in 1980 when the Federal Funds rate was set at 20.0% and investors could earn 16.0% on CDs, guess what? Stocks were logging their lowest valuation levels in decades (approximately 8x P/E ratio vs 17x today). The interest rate chart from Scott Grannis below highlights the near generational low interest rates we are currently experiencing.

Source: Calafia Beach Pundit

Sentiment: As I wrote in my Sentiment Indicators: Reading the Tea Leaves article, there are plenty of sentiment indicators (e.g., AAII Surveys, VIX Fear Gauge, Breadth Indicators, NYSE Bulls %, Put-Call Ratio, Volume), which traditionally are good contrarian indicators for the future direction of stock prices. When sentiment is too bullish (optimistic), it is often a good time to sell or trim, and when sentiment is too bearish (pessimistic), it is often good to buy. With that said, in addition to many of these short-term sentiment indicators, I realize that actions speak louder than words, therefore I like to also see the flows of funds into and out of stocks/bonds to gauge sentiment (see also Market Champagne Sits on Ice).

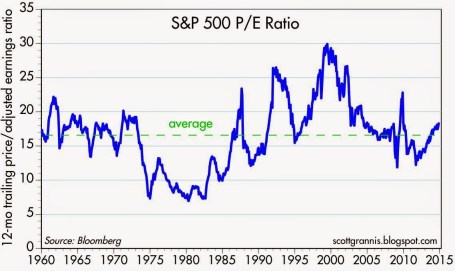

Valuations: As Fred Hickey, the lead editor of the High Tech Strategist noted, “Valuations do matter in the stock market, just as good pitching matters in baseball.” The most often quoted valuation metric is the Price/Earnings multiple or PE ratio. In other words, this ratio compares the price you would pay for an annual stream of profits. This can be tricky to determine because there are virtually an infinite number of factors that can impact the numerator and denominator. Currently P/E valuations are near historical averages (see below) – not nearly as cheap as 1980 and not nearly as expensive as 2000. If I only had one metric to choose, this would be a good place to start because the previous three legs of the stool feed into valuation calculations. In addition to P/E, at Sidoxia one of our other favorite metrics is Free-Cash-Flow Yield (annual cash generation after all expenses and expenditures divided by a company’s value). Earnings can be manipulated much easier than cold hard cash in our view.

Source: Calafia Beach Pundit

Nobody, myself and Warren Buffett included, can consistently predict what the stock market will do in the short-run. Buffett freely admits it. However, investing is a game of probabilities, and if you use the four tenets of profits, interest rates, sentiment, and valuations to drive your long-term investing decisions, your chances for future financial success will increase dramatically. This framework is just as relevant today as it is when studying the 1929 Crash, the 1989 Japan Bubble, or the 2008-2009 Financial Crisis. If your goal is to not become an investing fool, I highly encourage you to follow the legs of the Sidoxia stool.

Wade W. Slome, CFA, CFP®

Plan. Invest. Prosper.

DISCLOSURE: Sidoxia Capital Management (SCM) and some of its clients own a range of positions, including BAC and certain exchange traded fund positions, but at the time of publishing SCM had no direct position in any other security referenced in this article. No information accessed through the Investing Caffeine (IC) website constitutes investment, financial, legal, tax or other advice nor is to be relied on in making an investment or other decision. Please read disclosure language on IC Contact page.

No Free Lunch, No Free Sushi

Everybody loves a free lunch, myself included, and many in Japan would like free sushi too. Despite the short term boost in Japanese exports and Nikkei stock prices, there are no long-term free lunches (or free sushi) when it comes to global financial markets. Following in the footsteps of the U.S. Federal Reserve, the Bank of Japan (BOJ) has embarked on an ambitious plan of doubling its monetary base in two years and increasing inflation to a 2% annual rate – a feat that has not been achieved in more than two decades. By the BOJ’s estimate, it will take a $1.4 trillion injection into economy to achieve this goal by the end of 2014.

Lunch is tasty right now, as evidenced by a tasty appetizer of +3.5 % Japanese first quarter GDP and this year’s +46% spike in the value of the Nikkei. Japan is hopeful that its mix of monetary, fiscal, and structural policies will spur demand and increase the appetite for Japanese exports, however, we know fresh sushi can turn stale quickly.

Quantitative easing (QE) and monetary stimulus from central banks around the globe have been hailed as a panacea for sluggish global growth – most recently in Japan. Commentators often oversimplify the benefits of money printing without acknowledging the pitfalls. Basic economics and the laws of supply & demand eventually prevail no matter the fiscal or monetary policy implemented. Nonetheless, there can be temporary disconnects between current equity prices and exchange rates, before underlying fundamentals ultimately drive true intrinsic values.

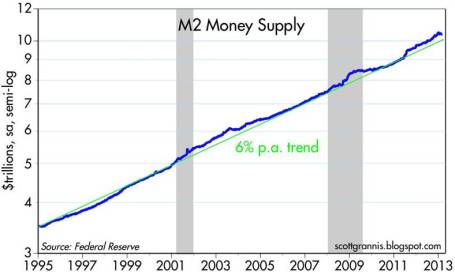

Impassioned critics of the Federal Reserve and its Chairman Ben Bernanke would have you believe the money supply is exploding, and hyperinflation is just around the corner. It’s difficult to quarrel with the trillions of dollars created by the Fed’s printing presses via QE1/QE2/QE3, but the fact remains that money supply growth has continued at a steady growth rate – not exploding (see Calafia Beach Pundit chart below).

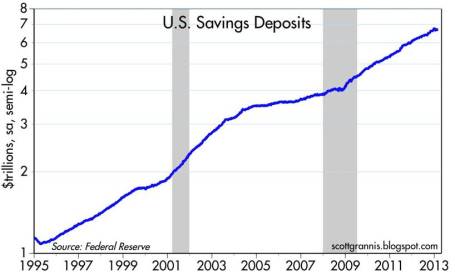

Why no explosion in the money supply? Simply, the trillions of dollars printed by the Fed have sat idly in bank vaults as reserves. Once nervous consumers stop hoarding trillions in cash held in savings deposit accounts (see chart below) and banks begin lending at a healthier clip, then money supply growth will accelerate. By definition, money supply growth in excess of demand for goods and services (i.e., GDP) is the main cause of inflation.

Although inflationary pressure has not reared its ugly head yet, there are plenty of precursors indicating inflation may be on its way. The unemployment rate continues to tick downwards (7.5% in Aril) and the much anticipating housing recovery is gaining steam. Inflationary fear has manifested itself in part through the heightened number of conversations surrounding the Fed “tapering” its $85 billion per month bond purchasing program.

We’ve enjoyed a sustained period of low price level growth, however the Goldilocks period of little-to-no inflation cannot last forever. The differences between current prices and true value can exist for years, and as a result there are many different strategies attempted to capture profits. Like the gambling masses frequenting casinos, speculators can beat the odds in the short-run, but the house always wins in the long-run – hence the ever-increasing size and number of casinos. While a small number of professionals understand how to shift the unbalanced odds into their favor, most lose their shirt. On Wall Street, that is certainly the case. Studies show speculating day traders persistently lose about 80% of the time. Long-term investors are uniquely positioned to exploit these value disparities, if they have a disciplined process with the ability to patiently value assets.

Even though the Japanese economy and stock market have rebounded handsomely in the short-run, there is never a free lunch over the long-term. Unchecked policies of money printing, deficits, and debt expansion won’t lead to boundless prosperity. Eventually a spate of irresponsible actions will result in inflation, defaults, recessions, and/or higher unemployment rates. Unsustainable monetary and fiscal stimulus may lead to a tasty free lunch now, but if investors overstay their welcome, the sushi may turn bad and the speculators will be left paying the hefty tab.

Wade W. Slome, CFA, CFP®

Plan. Invest. Prosper.

DISCLOSURE: Sidoxia Capital Management (SCM) and some of its clients hold positions in certain exchange traded funds (ETFs), but at the time of publishing SCM had no direct position in any other security referenced in this article. No information accessed through the Investing Caffeine (IC) website constitutes investment, financial, legal, tax or other advice nor is to be relied on in making an investment or other decision. Please read disclosure language on IC Contact page.

Crisis Delivers Black-Eye to Classic Economists

Markets are efficient. Individuals behave rationally. All information is reflected in prices. Huh…are you kidding me? These are the beliefs held by traditional free market economists (“rationalists”) like Eugene Fama (Economist at the University of Chicago and a.k.a. the “Father of the Efficient Market Hypothesis”). Striking blows to the rationalists are being thrown by “behavioralists” like Richard Thaler (Professor of Behavioral Science and Economics at the University of Chicago), who believes emotions often lead to suboptimal decisions and also thinks efficient market economics is a bunch of hogwash.

Individual investors, pensions, endowments, institutional investors, governments, are still sifting through the rubble in the aftermath of the 2008-2009 financial crisis. Experts and non-experts are still attempting to figure out how this mass destruction occurred and how it can be prevented in the future. Economists, as always, are happy to throw in their two cents. Right now traditional free market economists like Fama have received a black eye and are on the defensive – forced to explain to the behavioral finance economists (Thaler et. al.) how efficient markets could lead to such a disastrous outcome.

Religion and Economics

Like religious debates, economic rhetoric can get heated too. Religion can be divided up in into various categories (e.g., Christianity, Islam, Judaism, Hinduism, Buddhism, and other), or more simply religion can be divided into those who believe in a god (theism) and those who do not (atheism). There are multiple economic categorizations or schools as well (e.g., Keynsians, monetarism, libertarian, behavioral finance, etc.). Debates and disagreements across the rainbow of religions and economic schools have been going on for centuries, and the completion of the 2008-09 financial crisis has further ignited the battle between the “behavioralists” (behavioral finance economists) and the “rationalists” (traditional free market economists).

Behavioral Finance on the Offensive

In the efficient market world of the “rationalists,” market prices reflect all available information and cannot be wrong at any moment in time. Effectively, individuals are considered human calculators that optimize everything from interest rates and costs to benefits and inflation expectations in every decision. What classic economics does not include is emotions or behavioral flaws.

Purporting that financial market decisions are not impacted by emotions becomes more difficult to defend if you consider the countless irrational anomalies considered throughout history. Consider the following:

- Tulip Mania: Bubbles are nothing new – they have persisted for hundreds of years. Let’s reflect on the tulip bulb mania of the 1600s. For starters, I’m not sure how classic economists can explain the irrational exchanging of homes or a thousand pounds of cheese for a tulip bulb? Or how peak prices of $60,000+ in inflation-adjusted dollars were paid for a bulb at the time (C-Cynical)? These are tough questions to answer for the rationalists.

- Flash Crash: Seeing multiple stocks (i.e., ACN and EXC) and Exchange Traded Funds (ETFs) temporarily trade down -99% in minutes is not exactly efficient. Stalwarts like Procter & Gamble also collapsed -37%, only to rebound minutes later near pre-collapse levels. All this volatility doesn’t exactly ooze with efficiency (see Making Millions in Minutes).

- Negative T-Bill Rates: For certain periods of 2008 and 2009, investors earned negative yields on Treasury Bills. In essence, investors were paying the government to hold their money. Hmmm?

- Technology and Real Estate Bubbles: Both of these asset classes were considered “can’t lose” investments in the late 1990s and mid-2000s, respectively. Many tech stocks were trading at unfathomable values (more than 100 x’s annual profits) and homebuyers were inflating real estate prices because little to no money was required for the purchases.

- ’87 Crash: October 19, 1987 became infamously known as “Black Monday” since the Dow Jones Industrial Average plunged over -22% in one day (-508 points), the largest one-day percentage decline ever.

The list has the potential of going on forever, and the recent 2008-09 financial crisis only makes rationalists’ jobs tougher in refuting all this irrational behavior. Maybe the rationalists can use the same efficient market framework to help explain to my wife why I ate a whole box of Twinkies in one sitting?

Rationalist Rebuttal

The rationalists may have gotten a black eye, but they are not going down without a fight. Here are some quotes from Fama and fellow Chicago rationalist pals:

On the Crash-Related Attacks from Behavioralists: Behavioralists say traditional economics has failed in explaining the irrational decisions and actions leading up to the 2008-09 crash. Fama states, “I don’t see this as a failure of economics, but we need a whipping boy, and economists have always, kind of, been whipping boys, so they’re used to it. It’s fine.”

Rationalist Explanation of Behavioral Finance: Fama doesn’t deny the existence of irrational behavior, but rather believes rational and irrational behaviors can coexist. “Efficient markets can exist side by side with irrational behavior, as long as you have enough rational people to keep prices in line,” notes Fama. John Cochrane treats behavioral finance as a pseudo-science by replying, “The observation that people feel emotions means nothing. And if you’re going to just say markets went up because there was a wave of emotion, you’ve got nothing. That doesn’t tell us what circumstances are likely to make markets go up or down. That would not be a scientific theory.”

Description of Panics: “Panic” is not a term included in the dictionary of traditional economists. Fama retorts, “You can give it the charged word ‘panic,’ if you’d like, but in my view it’s just a change in tastes.” Calling these anomalous historic collapses a “change in tastes” is like calling Simon Cowell, formerly a judge on American Idol, “diplomatic.” More likely what’s really happening is these severe panics are driving investors’ changes in preferences.

Throwing in White Towel Regarding Crash: Not all classic economists are completely digging in their heels like Fama and Cochrane. Gary Becker, a rationalist disciple, acknowledges “Economists as a whole didn’t see it coming. So that’s a black mark on economics, and it’s not a very good mark for markets.”

Settling Dispute with Lab Rats

The boxing match continues, and the way the behavioralists would like to settle the score is through laboratory tests. In the documentary Mind Over Money, numerous laboratory experiments are run using human subjects to tease out emotional behaviors. Here are a few examples used by behavioralists to bolster their arguments:

- The $20 Bill Auction: Zach Burns, a professor at the University of Chicago, conducted an auction among his students for a $20 bill. Under the rules of the game, as expected, the highest bidder wins the $20 bill, but as an added wrinkle, Burns added the stipulation that the second highest bidder receives nothing but must still pay the amount of the losing bid. Traditional economists would conclude nobody would bid higher than $20. See the not-so rational auction results here at minute 1:45.

- $100 Today or $102 Tomorrow? This was the question posed to a group of shoppers in Chicago, but under two different scenarios. Under the first scenario, the individuals were asked whether they would prefer receiving $100 in a year from now (day 366) or $102 in a year and one additional day (day 367)? Under the second scenario, the individuals were asked whether they would prefer receiving $100 today or $102 tomorrow? The rational response to both scenarios would be to select $102 under both scenarios. See how the participants responded to the questions here at minute 4:30.

Rationalist John Cochrane is not fully convinced. “These experiments are very interesting, and I find them interesting, too. The next question is, to what extent does what we find in the lab translate into how people…understanding how people behave in the real world…and then make that transition to, ‘Does this explain market-wide phenomenon?,’” he asks.

As alluded to earlier, religion, politics, and economics will never fall under one universal consensus view. The classic rationalist economists, like Eugene Fama, have in aggregate been on the defensive and taken a left-hook in the eye for failing to predict and cohesively explain the financial crash of 2008-09. On the other hand, Richard Thaler and his behavioral finance buds will continue on the offensive, consistently swinging at the classic economists over this key economic mind versus money dispute.

See Complete Mind Over Money Program

Wade W. Slome, CFA, CFP®

Plan. Invest. Prosper.

DISCLOSURE: Sidoxia Capital Management (SCM) and some of its clients own certain exchange traded funds, but at the time of publishing SCM had no direct position in ACN, EXC, or any other security referenced in this article. No information accessed through the Investing Caffeine (IC) website constitutes investment, financial, legal, tax or other advice nor is to be relied on in making an investment or other decision. Please read disclosure language on IC “Contact” page.

Productivity & Trade: Pins, Cars, Coconuts & Chips

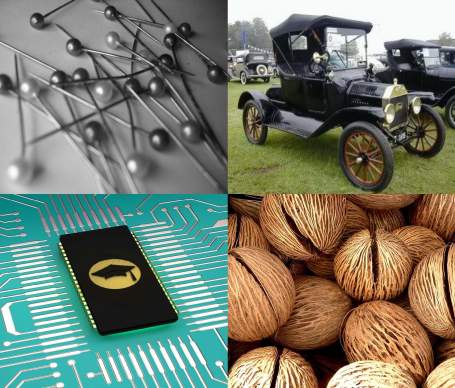

The concepts of productivity and free trade go all the way back to Adam Smith, widely considered the “father of economics,” who wrote the original capitalism Bible called the Wealth of Nations. Many of the same principles discussed in Smith’s historic book are just as applicable today as they were in 1776 when it was first published.

Economics at its core is the thirst for efficiency and productivity for the sake of profits. Ultimately, for the countries that successfully practice these principles, a higher standard of living can be achieved for its population. For the U.S. to thrive in the 21st century like we did in the 20th century, we need to embrace productive technology and efficiently integrate proven complex systems. To illustrate the benefits of productivity in a factory setting, Smith wrote about the division of labor in a pin factory. Murray N. Rothbard, an economic historian, and political philosopher summed up the takeaways here:

“A small pin-factory where ten workers, each specializing in a different aspect of the work [18 steps], could produce over 48,000 pins a day, whereas if each of these ten had made the entire pin on his own, they might not have made even one pin a day, and certainly not more than 20.”

Dividing up the 18 pin making steps (i.e., pull wire, cut wire, straighten wire, put on head, paint, etc.) lead to massive productivity improvements.

Another economic genius that changed the world we live in is the father of mass production…Henry Ford. He revolutionized the car industry by starting the Ford Motor Company in 1903 with $100,000 in capital and 12 shareholders. By the beginning of 1904, Ford Motors had sold about 600 cars and by 1924 Ford reached a peak production of more than 2,000,000 cars, trucks, and tractors per year. Although, Ford had a dominant market share here in the U.S., the innovative technology and manufacturing processes allowed him to profit even more by exporting cars internationally. This transformation of the automobile industry allowed Ford to hire thousands of workers with handsome wages and spread 15 million of his cars around the globe from 1908 to 1927.

Comparative Advantage: Lessons from Smith & Ford

Foreign trade has continually been a hot button issue – especially during periods of softer global economic activity. Here is what Adam Smith had to add on the subject:

“If a foreign country can supply us with a commodity cheaper than we ourselves can make it, better buy it of them with some part of the produce of our own industry, employed in a way in which we have some advantage.”

Smith believed that parties with an “absolute advantage” in manufacturing would benefit by trading with other partners. Today, it’s fairly clear the U.S. has an absolute advantage in creating biotech drugs, Hollywood movies, and internet technologies (i.e., Google), however in other industries, such as industrial manufacturing, the U.S. has lost its dominant position.

David Ricardo, an English economist who authored the famous work On the Principles of Political Economy and Taxation, is attributed with extending Smith’s “absolute advantage” concept one step further by introducing the idea of “comparative advantage.”

Producing Coconuts and Computer Chips

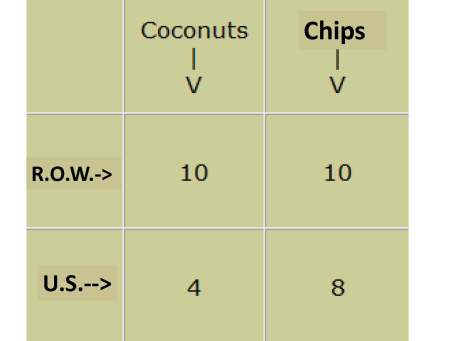

Let’s explore the comparative advantage concept some more by investigating coconuts and computer chips. As we hemorrhage jobs to other countries that can accomplish work more cheaply and efficiently, increasingly discussions shift to a more protectionist stance with dreams of higher import tariffs. Is this a healthy approach? Consider a two nation island able to produce only two goods (coconuts and computer “chips”), with the U.S. on one half of the island, and the Rest of the World (R.O.W.) on the other half.

Next, let’s assume the following production profile: The R.O.W. can choose to produce 10 coconuts or 10 chips AND the U.S. can produce 4 coconuts or 8 chips.

Scenario #1 (No Trade): If we assume both the R.O.W. and the U.S. each spend half their time producing coconuts and chips, then the R.O.W.’s production will create 5 coconuts/5 chips and the U.S. 2 coconuts/4 chips for a combined total of 7 coconuts and 9 chips (16 overall units).

If we were to contemplate the ability of trade between R.O.W. and the U.S., coupled with the concept of comparative advantage, we may see overall productivity of the nation island improve. Despite the R.O.W. having an “absolute advantage” over the U.S. in producing both coconuts (10 vs. 4) and chips (10 vs. 8), the next example demonstrates trade is indeed beneficial.

Scenario #2 (With Trade): If R.O.W. uses its comparative advantage (“more better”) to produce 10 coconuts and the U.S. uses its comparative advantage (“less worse”) to produce 8 chips for a combined total of 10 coconuts and 8 chips (18 overall units). Relative to Scenario #1, this example produces 12.5% more units (18 vs. 16) and with the ability of trade, the U.S. and R.O.W. should be able to optimize the 18 units to meet their individual country preferences.

If we can successfully escape from the island and paddle back to modern times, we can better understand the challenges we face as a country in the current flat global world we live in. Our lack of investment into education, innovation, and next generation infrastructure is making us less competitive in legacy rustbelt industries, such as in automobiles and general manufacturing. If the goal is to maximize productivity, efficiency, and our country’s standard of living, then it makes sense to select trade scenario #2 (even if it means producing zero coconuts and lots of computer chips). The coconut lobby may not be happy under this scenario, but more jobs will be created from higher output and trade while our citizens continue on a path to a higher standard of living.

The free trade strategy will only work if we can motivate, train, and educate enough people into higher paying jobs that produce higher value added products and services (e.g., computer chips and computer consulting). There is a woeful shortage of engineers and scientists in our country, and if we want to compete successfully in the modern world against the billions of people scratching and clawing for our standard of living, then we need to openly accept the productivity and trade principles taught to us by the Adam Smiths and Henry Fords of the world. Otherwise, be prepared to live on a remote, isolated island with a steady diet of coconuts for breakfast, lunch, and dinner.

Read Full NetMBA Article on “Comparative Advantage”

Wade W. Slome, CFA, CFP®

Plan. Invest. Prosper.

*DISCLOSURE: Sidoxia Capital Management (SCM) and some of its clients own certain exchange traded funds and GOOG, but at the time of publishing SCM had no direct position in any other security referenced in this article. No information accessed through the Investing Caffeine (IC) website constitutes investment, financial, legal, tax or other advice nor is to be relied on in making an investment or other decision. Please read disclosure language on IC “Contact” page.

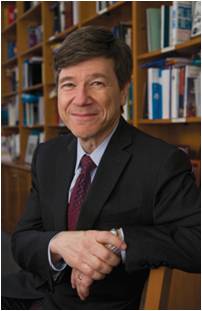

Sachs Prescribes Telescope Over Microscope

Jeffrey Sachs, Professor at Columbia University and one of Time magazine’s “100 most influential people” recommends that our country takes a longer-term view in handling our problems (read Sachs’s full bio). Instead of analyzing everything through a microscope, Sachs realizes that peering out over the horizon with a telescope may provide a clearer path to success versus getting sidetracked in the emotional daily battles of noise.

I do my fair share of media and politician bashing, but every once in a while it’s magnificent to discover and enjoy a breath of fresh common sense, like the advice coming from Sachs. Normally, I become suffocated with a wet blanket of incessant, hyper-sensitive blabbering that comes from Washington politicians and airwave commentators. With the advent of this thing we call the “internet,” the pace and volume of daily information (see TMI “Too Much Information” article) crossing our eyeballs has only snowballed faster. Rather than critically evaluate the fear-laced news, the average citizen reverts back to our Darwinian survival instincts, or to what Seth Godin calls the “Lizard Brain. ”

Sachs understands the lingering nature to our country’s problems, so in pulling out his long-term telescope, he created a broad roadmap to recovery – many of the points to which I agree. Here is an abbreviated list of his quotes:

On Short-Termism:

“Despite the evident need for a rise in national saving after 2008, President Barack Obama tried to prolong the consumption binge by aggressively promoting home and car sales to already exhausted consumers, and by cutting taxes despite an unsustainable budget deficit. The approach has been hyper short-term, driven by America’s two-year election cycle. It has stalled because US consumers are taking a longer-term view than the politicians.”

On Differences between China and the U.S.:

“China saves and invests; the US talks, consumes, borrows, and talks some more.”

On Why Tax Cuts and Stimulus Alone Won’t Work:

“Short-term tax cuts or transfers on top of America’s $1,500bn budget deficit are unlikely to do much to boost demand, while they would greatly increase anxieties over future fiscal retrenchment. Households are hunkering down, and many will regard an added transfer payment as a temporary windfall that is best used to pay down debt, not boost spending.”

On Malaise Hampering Businesses:

“Businesses, for their part, are distressed by the lack of direction….Uncertainty is a real killer.”

On 5-Point Plan to a U.S. Recovery:

1) Increased Clean Energy Investments: The recovery needs “a significant boost in investments in clean energy and an upgraded national power grid.”

2) Infrastructure Upgrade: “A decade-long program of infrastructure renovation, with projects such as high-speed inter-city rail, water and waste treatment facilities and highway upgrading, co-financed by the federal government, local governments and private capital.”

3) Further Education: “More education spending at secondary, vocation and bachelor-degree levels, to recognize the reality that tens of millions of American workers lack the advanced skills needed to achieve full employment at the salaries that the workers expect.”

4) Infrastructure Exports to the Poor: “Boost infrastructure exports to Africa and other low-income countries. China is running circles around the US and Europe in promoting such exports of infrastructure. The costs are modest – essentially just credit guarantees – but the benefits are huge, in increased exports, support for African development and a boost in geopolitical goodwill and stability.”

5) Deficit Reduction Plan: “A medium-term fiscal framework that will credibly reduce the federal budget deficit to sustainable levels within five years. This can be achieved partly by cutting defense spending by two percentage points of gross domestic product.”

Rather than succumb to the nanosecond, fear-induced headlines that rattle off like rapid fire bullets, Sachs supplies thoughtful long-term oriented solutions and ideas. The fact that Sachs mentions the word “decade” three times in his Op-ed highlights the lasting nature of these serious problems our country faces. To better see and deal with these challenges more clearly, I suggest you borrow Sachs’s telescope, and leave the microscope in the lab.

Read Full Financial Times Article by Jeffrey Sachs

Wade W. Slome, CFA, CFP®

Plan. Invest. Prosper.

*DISCLOSURE: Sidoxia Capital Management (SCM) and some of its clients own certain exchange traded funds, but at the time of publishing SCM had no direct position in any security referenced in this article. No information accessed through the Investing Caffeine (IC) website constitutes investment, financial, legal, tax or other advice nor is to be relied on in making an investment or other decision. Please read disclosure language on IC “Contact” page.

Margin Surplus Retake

Like a B-rated horror movie using the same old cliques (i.e., girl home alone with serial killer on the loose or a concealed intruder hidden in the back seat of a car), one of the financial cliques that persists today is the belief that the United States trade deficit will result in financial ruin for our economy. The recent widening of the trade deficit to $40.3 billion makes this economic issue a topical discussion. Enter Andy Kessler, former hedge fund manager and author of Running Money. He believes the stale, exploding trade deficit arguments are hogwash, primarily due to his “margin surplus” theory articulated in his book and Wall Street Journal article entitled, We Think, They Sweat.

Profiting from Trade Deficits

The absolute numbers used by Kessler in his Toshiba laptop example might have changed since his book was first published in 2004, but this margin surplus theory example is just as relevant today as it was back then. Here is an excerpt from his book:

“Let’s open up that Toshiba laptop. With a $300 Intel chip (which has at least $250 in profit for Intel) and a $50 Windows license ($49.95 margin to Microsoft), the laptop is then sold by Toshiba back into the U.S. for $1,000. Toshiba and every other supplier are lucky if they make $50 profit, combined, on the deal.”

In this illustration, government statistics would recognize a $1,000 contribution to our bloating trade deficit figures, even though nearly 90% of the laptop profits would be flowing (“surplus-ing”) back to the U.S. Hmmm, maybe this trade deficit thing isn’t as evil as it is portrayed in the popular media, or perhaps we are measuring it incorrectly? Kessler makes the case that Gross Domestic Product (GDP) is not the most important economic gauge, but rather the real crucial GDP metric is actually Gross Domestic PROFIT. He adds the best indicator for economic profits is the stock market, and as foreigners seek more productive returns on their cash beyond the 3% Treasury yields, they will eventually filter back their dollar currency reserves into stocks and other more productive asset classes.

Brain Driven Economy

You don’t have to be a brain surgeon to realize our roots as an industrial economy have shifted to an intellectual property economy. So while we may be exporting low-skilled labor jobs to China and other low-cost regions, our country is also creating higher-skilled, higher-paying jobs at innovative growing companies such as Google Inc. (GOOG) and Apple Inc. (AAPL). Case in point, flip an Apple iPod over and read the fine print on the back – it reads, “Assembled in China…Designed by Apple in California.” Once again, the commoditized aspects of slapping together a widget have been outsourced to workers in far-off lands for a small fraction of what American workers earn. If improving the standard of living is our goal, then transferring low paying jobs to foreigners should not be a concern. According to Kessler, $70 in iPod profits (versus $4 for the Chinese assemblers) from this unique, differentiated device has generated millions in profits, which in turn can be used for the creation of desirable, high-paying jobs here in the U.S.

Selling the Farm

Warren Buffets has a different view about our trade deficits and the directional value of the U.S. dollar. He perceives our economy as a fixed size farm that is selling $2 billion pieces of the farm to foreigners on a daily basis. Buffet adds:

“We’re like a very rich family; we own a farm the size of Texas but want to consume more. If you force-feed $2 billion a day to the rest of the world, they get somewhat less enthusiastic over time – and the dollar is worth less.”

Over time, Buffett believes future generations will resent paying for the gluttony of consumption by prior generations and foreigners will demand a higher interest rate for their loans. What I believe Buffet fails to consider is that the farm is not static. As we sell off $2 billion chunks of the farm, portions of those proceeds are being used to adjoin additions, buy new farms, build adjacent wind turbines, and/or incorporate other productive uses. Now if the proceeds were used to solely purchase bon-bons and doughnuts, then indeed we would be in trouble. Ultimately, the financial markets will be the true arbiter of how efficiently the foreign capital is being invested and will dictate the level of rates paid on the loans. From a pure cash management standpoint, stretching out payables (net imports) is a sound practice (i.e., it’s desirable to collect early and pay late).

The flip side of the argument explains how the farm sale proceeds from our asset sales to foreigners (such as our real estate, our Treasuries, and our stocks) can be employed in a productive manner. The Buffett argument states that our farm will eventually be completely sold to foreigners or they will hold a gun to our head asking for higher interest rates to fund our deficits. The problem with that argument is that the money received from the farm sales (Treasuries, stocks, real estate, etc.) can be (and is) used to build new farms. And that is the key question…are all these deficit building dollars being used to create new, innovative, job creating companies like Google and Apple, or are these dollars being redeployed into unproductive uses (e.g., worthless t-shirts and lead-filled toys from China, or funding of bailouts and cash-for-clunkers waste) ?

At the end of the day, money goes where it is treated best – meaning global capital seeks the royal treatment in markets where profits reign supreme. So rather than relying on rusty, obsolete statistics measuring the balance of trade (i.e., trade deficits and GDP), investors would be better served by taking a page from Andy Kessler’s book. Following the principles of “margin surplus” will increase the probabilities of profiting from global capital flows.

Wade W. Slome, CFA, CFP®

Plan. Invest. Prosper.

*DISCLOSURE: Sidoxia Capital Management (SCM) and some of its clients own certain exchange traded funds, Treasury securities, GOOG, and AAPL, but at the time of publishing SCM had no direct positions in Toshiba, INTC, BRKA/B or any other security referenced in this article. No information accessed through the Investing Caffeine (IC) website constitutes investment, financial, legal, tax or other advice nor is to be relied on in making an investment or other decision. Please read disclosure language on IC “Contact” page.

Friedman Looks to Flatten Problems in Flat World

Thomas Friedman, author of recent book Hot, Flat, and Crowded and New York Times columnist, combines a multi-discipline framework in analyzing some of the most complex issues facing our country, from both an economic and political perspective. Friedman’s distinctive lens he uses to assimilate the world, coupled with his exceptional ability of breaking down and articulating these thorny challenges into bite-sized stories and analogies, makes him a one-of-a-kind journalist. Whether it’s explaining the history of war through McDonald’s hamburgers, or using the Virgin Guadalupe to explain the rise of China, Friedman brings highbrow issues down to the eye-level of most Americans.

In his seminal book, The World is Flat, Friedman explains how technology has flattened the global economy to a point where U.S. workers are fighting to keep their domestic tax preparation and software engineering jobs, as new emerging middle classes from developing countries, like China and India, steal work.

The Flat World

In boiling down the recent financial crisis, Friedman used Iceland to explain the “flattening” of the globe:

“Fifteen British police departments lost all their money in Icelandic online savings accounts. Like who knew? I knew the world was flat – I didn’t know it was that flat…that Iceland would become a hedge fund with glaciers.”

The left-leaning journalist hasn’t been afraid to bounce over to the “right” when it comes to foreign affairs and certain fiscally conservative issues. For example, he initially full-heartedly supported George W. Bush’s invasion of Iraq. And on global trade, he has a stronger appreciation of the economic benefits of free trade as compared to traditionally Democratic protectionist views.

Calling All Better Citizens

In a recent Charlie Rose interview, Friedman’s patience with our country’s citizenry has worn thin – he believes government leaders cannot be relied on to solve our problems.

When it comes to the massive deficits and foreign affair issues, Friedman comes to the conclusion we need to cut expenses or raise taxes. By creating a $1 per gallon gasoline tax, Friedman sees a “win-win-win-win” solution. Not only could the country wean itself off foreign oil addiction from authoritarian governments and create scores of new jobs with E.T. (Energy Technologies), the tax could also raise money to reduce our fiscal deficit, and pay for expanded healthcare coverage.

It’s fairly clear to me that government can’t show the leadership in cutting expenses. Since cutting benefits for voters won’t get you re-elected, taxes most certainly will have to go up. Wishful thinking that a recovering economy will do the dirty, debt-cutting work is probably naïve. If forced to pick a poison, the gas tax is Friedman’s choice. I’m not so sure the energy lobby would feel the same?

Political gridlock has always been an obstacle for getting things done in Washington. Technology, scientific polling, 24/7 news cycles, and deep-pocketed lobbyists are only making it tougher for our country to deal with our difficult challenges. Regardless of whether Friedman’s gasoline tax is the silver bullet, I welcome the clear, passionate voice from somebody that understands the challenges of living in a flat world.

Wade W. Slome, CFA, CFP®

Plan. Invest. Prosper.

DISCLOSURE: Sidoxia Capital Management (SCM) owns certain exchange traded funds (BKF, FXI) and has a short position in MCD at the time this article was originally posted. No information accessed through the Investing Caffeine (IC) website constitutes investment, financial, legal, tax or other advice nor is to be relied on in making an investment or other decision. Please read disclosure language on IC “Contact” page.