Posts tagged ‘Accounting’

A Recipe for Disaster

Justice does not always get served in the stock market because financial markets are not always efficient in the short-run (see Black-Eyes to Classic Economists). However, over the long-run, financial markets usually get it right. And when the laws of economics and physics are functioning properly, I must admit it, I do find it especially refreshing.

There can be numerous reasons for stocks to plummet in price, but common attributes to stock price declines often include profit losses and/or disproportionately high valuations (a.k.a. “bubbles”). Normally, your garden variety, recipe for disaster consists of one part highly valued company and one part money-losing operation (or deteriorating financials). The reverse holds true for a winning stock recipe. Flavorful results usually involve cheaply valued stocks paired with improving financial results.

Unfortunately, just because you have the proper recipe of investment ingredients, doesn’t mean you will immediately get to enjoy a satisfying feast. In other words, there isn’t a dinner bell rung to signal the timing of a crash or spike – sometimes there is a conspicuous catalyst and sometimes there is not. Frequently, investments require a longer expected bake time before the anticipated output is produced.

As I alluded to at the beginning of my post, justice is not always served immediately, but for some high profile IPOs, low-quality ingredients have indeed produced low-quality results.

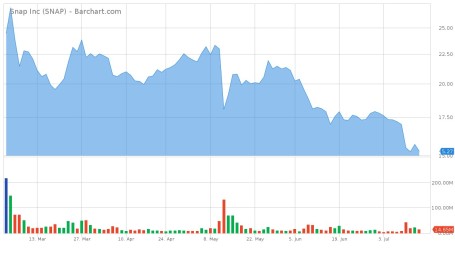

Snap Inc. (SNAP): Let’s first start with the high-flying social media darling Snap, which priced its IPO at $17 per share in March, earlier this year. How can a beloved social media company that generates $515 million in annual revenue (up +286% in the recent quarter) see its stock plummet -48% from its high of $29.44 to $15.27 in just four short months? Well, one way of achieving these dismal results is to burn through more cash than you’re generating in revenue. Snap actually scorched through more than -$745 million dollars over the last year, as the company reported accounting losses of -$618 million (excluding -$2 billion of stock-based compensation expenses). We’ll find out if the financial bleeding will eventually stop, but even after this year’s stock price crash, investors are still giving the company the benefit of the doubt by valuing the company at $18 billion today.

Source: Barchart.com

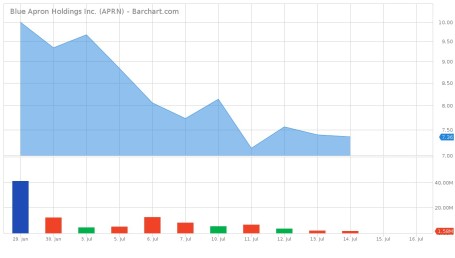

Blue Apron Holdings Inc. (APRN): Online meal delivery favorite, Blue Apron, is another company suffering from the post-IPO blues. After initially targeting an opening IPO price of $15-$17 per share a few weeks ago, tepid demand forced Blue Apron executives to cut the price to $10. Fast forward to today, and the stock closed at $7.36, down -26% from the IPO price, and -57% below the high-end of the originally planned range. Although the company isn’t hemorrhaging losses at the same absolute level of Snap, it’s not a pretty picture. Blue Apron has still managed to burn -$83 million of cash on $795 million in annual sales. Unlike Snap (high margin advertising revenues), Blue Apron will become a low-profit margin business, even if the company has the fortune of reaching high volume scale. Even after considering Blue Apron’s $1 billion annual revenue run rate, which is 50% greater than Snap’s $600 million run-rate, Blue Apron’s $1.4 billion market value is sadly less than 10% of Snap’s market value.

Source: Barchart.com

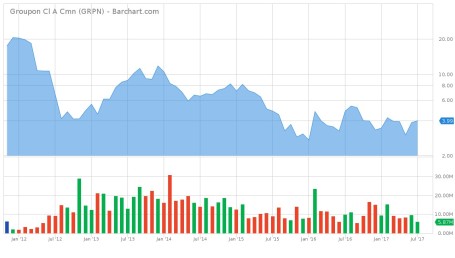

Groupon Inc. (GRPN): Unlike Snap and Blue Apron, Groupon also has the flattering distinction of reporting an accounting profit, albeit a small one. However, on a cash-based analysis, Groupon looks a little better than the previous two companies mentioned, if you consider an annual -$7 million cash burn “better”. Competition in the online discounting space has been fierce, and as such, Groupon has experienced a competitive haircut in its share price. Groupon’s original IPO price was $20 in January 2011 before briefly spiking to $31. Today, the stock has languished to $4 (-87% from the 2011 peak).

Source: Barchart.com

Stock Market Recipe?

Similar ingredients (i.e., valuations and profit trajectory) that apply to stock performance also apply to stock market performance. Despite record corporate profits (growing double digits), low unemployment, low inflation, low-interest rates, and a recovering global economy, bears and even rational observers have been worried about a looming market crash. Not only have the broader masses been worried today, yesterday, last week, last month, and last year, but they have also been worried for the last nine years. As I have documented repeatedly (see also Market Champagne Sits on Ice), the market has more than tripled to new record highs since early 2009, despite the strong under-current of endless cynicism.

Historically market tops have been marked by a period of excesses, including excessive emotions (i.e., euphoria). It has been a long time since the last recession, but economic downturns are also often marked with excessive leverage (e.g., housing in the mid-2000s), excessive capital (e.g., technology IPOs [Initial Public Offerings] in the late-1990s), and excessive investment (e.g., construction / manufacturing in early-1990s).

To date, we have seen little evidence of these markers. Certainly there have been pockets of excesses, including overpriced billion dollar tech unicorns (see Dying Unicorns), exorbitant commercial real estate prices, and a bubble in global sovereign debt, but on a broad basis, I have consistently said stocks are reasonably priced in light of record-low interest rates, a view also held by Warren Buffett.

The key lessons to learn, whether you are investing in individual stocks or the stock market more broadly, are that prices will follow the direction of earnings over the long-run. This helps explain why stock prices always go down in recessions (and are volatile in anticipation of recessions).

If you are looking for a recipe for disaster, just find an overpriced investment with money-losing (or deteriorating) characteristics. Avoiding these investments and identifying investments with cheap growth qualities is much easier said than done. However, by mixing an objective, quantitative framework with more artistic fundamental analysis, you will be in a position of enjoying tastier returns.

Wade W. Slome, CFA, CFP®

Plan. Invest. Prosper.

DISCLOSURE: Sidoxia Capital Management (SCM) and some of its clients hold positions in certain exchange traded funds (ETFs), but at the time of publishing, SCM had no direct position in SNAP, APRN, GRPN, or any other security referenced in this article. No information accessed through the Investing Caffeine (IC) website constitutes investment, financial, legal, tax or other advice nor is the information to be relied on in making an investment or other decision. Please read disclosure language on IC Contact page.

EBITDA: Sniffing Out the Truth

Financial analysts are constantly seeking the Holy Grail when it comes to financial metrics, and to some financial number crunchers, EBITDA (Earnings Before Interest Taxes Depreciation and Amortization – pronounced “eebit-dah”) fits the bill. On the flip side, Warren Buffett’s right hand man Charlie Munger advises investors to replace EBITDA with the words “bullsh*t earnings” every time you encounter this earnings metric. We’ll explore the good, bad, and ugly attributes of this somewhat controversial financial metric.

The Genesis of EBITDA

The origin of the EBITDA measure can be traced back many years, and rose in popularity during the technology boom of the 1990s. “New Economy” companies were producing very little income, so investment bankers became creative in how they defined profits. Under the guise of comparability, a company with debt (Company X) that was paying high interest expenses could not be compared on an operational profit basis with a closely related company that operated with NO debt (Company Z). In other words, two identical companies could be selling the same number of widgets at the same prices and have the same cost structure and operating income, but the company with debt on their balance sheet would have a different (lower) net income. The investment banker and company X’s answer to this apparent conundrum was to simply compare the operating earnings or EBIT (Earnings Before Interest and Taxes) of each company (X and Z), rather than the disparate net incomes.

The Advantages of EBITDA

Although there is no silver bullet metric in financial statement analysis, nevertheless there are numerous benefits to using EBITDA. Here are a few:

- Operational Comparability: As implied above, EBITDA allows comparability across a wide swath of companies. Accounting standards provide leniency in the application of financial statements, therefore using EBITDA allows apples-to-apples comparisons and relieves accounting discrepancies on items such as depreciation, tax rates, and financing choice.

- Cash Flow Proxy:Since the income statement traditionally is the financial statement of choice, EBITDA can be easily derived from this statement and provides a simple proxy for cash generation in the absence of other data.

- Debt Coverage Ratios:In many lender contracts, certain debt provisions require specific levels of income cushion above the required interest expense payments. Evaluating EBITDA coverage ratios across companies assists analysts in determining which businesses are more likely to default on their debt obligations.

The Disadvantages of EBITDA

While EBITDA offers some benefits in comparing a broader set of companies across industries, the metric also carries some drawbacks.

- Overstates Income: To Charlie Munger’s point about the B.S. factor, EBITDA distorts reality by measuring income before a bunch of expenses. From an equity holder’s standpoint, in most instances, investors are most concerned about the level of income and cash flow available AFTERaccounting for all expenses, including interest expense, depreciation expense, and income tax expense.

- Neglects Working Capital Requirements: EBITDA may actually be a decent proxy for cash flows for many companies, however this profit measure does not account for the working capital needs of a business. For example, companies reporting high EBITDA figures may actually have dramatically lower cash flows once working capital requirements (i.e., inventories, receivables, payables) are tabulated.

- Poor for Valuation: Investment bankers push for more generous EBITDA valuation multiples because it serves the bankers’ and clients’ best interests. However, the fact of the matter is that companies with debt or aggressive depreciation schedules do deserve lower valuations compared to debt-free counterparts (assuming all else equal).

Wading through the treacherous waters of accounting metrics can be a dangerous game. Despite some of EBITDA’s comparability benefits, and as much as bankers and analysts would like to use this very forgiving income metric, beware of EBITDA’s shortcomings. Although most analysts are looking for the one-size-fits-all number, the reality of the situation is a variety of methods need to be used to gain a more accurate financial picture of a company. If EBITDA is the only calculation driving your analysis, I urge you to follow Charlie Munger’s advice and plug your nose.

Wade W. Slome, CFA, CFP®

Plan. Invest. Prosper.

DISCLOSURE: Sidoxia Capital Management (SCM) and some of its clients hold positions in certain exchange traded funds (ETFs), but at the time of publishing had no direct position in any other security referenced in this article. No information accessed through the Investing Caffeine (IC) website constitutes investment, financial, legal, tax or other advice nor is to be relied on in making an investment or other decision. Please read disclosure language on IC Contact page.

Monitoring the Tricks Hidden Up Corporate Sleeves

As Warren Buffett correctly states, “If you are in a poker game and after 20 minutes, you don’t know who the patsy is, then you are the patsy.” The same principle applies to investing and financial analysis. If you are unable to determine who is cooking (or warming) the books via deceptive practices, then you will be left holding a bag of losses as tears of regret pour down your face. The name of the stock investing game (not speculation game) is to accurately gauge the financial condition of a company and then to correctly forecast the trajectory of future earnings and cash flows.

Unfortunately for investors, many companies work quite diligently to obscure, hide, and distort the accuracy of their current financial condition. Without the ability of making a proper assessment of a company’s financials, an investor by definition will be unable to value stocks.

There are scores of accounting tricks that companies hide up their sleeves to mislead investors. Many people consider GAAP (Generally Accepted Accounting Principles) as the laws or rules governing financial reporting, but GAAP parameters actually provide companies with extensive latitude in the way accounting reports are implemented. Here are a few of the ways companies exercise their wiggle room in disclosing financial results:

Depreciation Schedules: Related to GAAP accounting, adjustments to longevity estimates by a company’s management team can tremendously impact a company’s reported earnings. For example, if a $10 million manufacturing plant is expected to last 10 years, then the depreciation expense should be $1 million per year ($10m ÷ 10 years). If for some reason the Chief Financial Officer (CFO) suddenly changes his/her mind and decides the building should last 40 years rather than 10 years, then the company’s annual expense would miraculously decrease -75% to $250,000. Voila, an instant $750,000 annual gain created out of thin air! Other depreciation tricks include the choice of accelerated or straight-line depreciation.

Capitalizing Expenses: If you were a management team member with a goal of maximizing current reported profitability, would you be excited to learn that you are not required to report expenses on your income statement? For many the answer is absolutely “yes”. A common example of this phenomenon occurs with companies in the software industry (or other companies with heavy research and development), where research expenses normally recognized on the income statement get converted instead to capitalized assets on the balance sheet. Eventually these capitalized assets get amortized (recognized as expenses) on the income statement. Proponents argue capitalizing expenses better matches future revenues to future expenses, but regardless, this scheme boosts current reported earnings, and delays expense recognition.

Stuffing the Channel: No, this is not a personal problem, but rather occurs when companies force their goods on a distributor or customer – even if the goods (or service) are not requested. This deceitful practice is performed to drive up short-term revenue, even if the reporting company receives no cash for the “stuffing”. Ballooning receivables and substandard cash flow generation can be a sign of this cunning, corporate custom.

Accounts Receivable/Loans: Ballooning receivables is a potential sign of juiced reported revenues and profits, but there are more nuanced ways of manipulating income. For instance, if management temporarily lowers warranty expenses and product return assumptions, short-term profits can be artificially boosted. In addition, when discussing financial figures for banks, loans can also be considered receivables. As we experienced in the last financial crisis, many banks under-provisioned for future bad loans (i.e. didn’t create enough cash reserves for misled/deadbeat borrowers), thereby overstating the true, underlying, fundamental earnings power of the banks.

Inventories: As it relates to inventories, GAAP accounting allows for FIFO (First-In, First-Out) or LIFO (Last-In, Last-Out) recognition of expenses. Depending on whether prices of inventories are rising or falling, the choice of accounting method could boost reported results.

Pension Assumptions: Most companies like their employees…but not the expenses they have to pay in order to keep them. Employee expenses can become excessively burdensome, especially for those companies offering their employees a defined benefit pension plan. GAAP rules mandate employers to contribute cash to the pension plan (i.e., retirement fund) if the returns earned on the assets (i.e., stocks & bonds) are below previous company assumptions. One temporary fix to an underfunded pension is for companies to assume higher plan returns in the future. For example, if companies raise their return assumptions on plan assets from 5% to a higher rate of 10%, then profits for the company are likely to rise, all else equal.

Non-GAAP (or Pro Forma): Why would companies report Non-GAAP numbers on their financial reports rather than GAAP earnings? The simple answer is that Non-GAAP numbers appear cosmetically higher than GAAP figures, and therefore preferred by companies for investor dissemination purposes.

Merger Magic: Typically when a merger or acquisition takes place, the acquiring company announces a bunch of one-time expenses that they want investors to ignore. Since there are so many moving pieces in a merger, that means there is also more opportunities to use smoke and mirrors. The recent $8.8 billion write-off of Hewlett-Packard’s (HPQ) acquisition of Autonomy is evidence of merger magic performed.

EBITDA (Earnings Before Interest Taxes Depreciation & Amortization): Skeptics, like myself, call this metric “earnings before all expenses.” Or as Charlie Munger says, Warren Buffett’s right-hand man, “Every time you see the word EBITDA, substitute it with the words ‘bulls*it earnings’!”

This is only a short-list of corporate accounting gimmicks used to distort financial results, so for the sake of your investment portfolio, please check for any potential tricks up a company’s sleeve before making an investment.

Wade W. Slome, CFA, CFP®

Plan. Invest. Prosper.

DISCLOSURE: Sidoxia Capital Management (SCM) and some of its clients hold positions in certain exchange traded funds (ETFs), but at the time of publishing SCM had no direct position in HPQ/Autonomy, or any other security referenced in this article. No information accessed through the Investing Caffeine (IC) website constitutes investment, financial, legal, tax or other advice nor is to be relied on in making an investment or other decision. Please read disclosure language on IC Contact page.

EBITDA: Sniffing Out the Truth

Financial analysts are constantly seeking the Holy Grail when it comes to financial metrics, and to some financial number crunchers EBITDA (Earnings Before Interest Taxes Depreciation and Amortization – pronounced “eebit-dah”) fits the bill. On the flip side, Warren Buffett’s right hand man Charlie Munger advises investors to replace EBITDA with the words “bullsh*t earnings” every time you encounter this earnings metric. We’ll explore the good, bad, and ugly attributes of this somewhat controversial financial metric.

The Genesis of EBITDA

The origin of the EBITDA measure can be traced back many years, and rose in popularity during the technology boom of the 1990s. “New Economy” companies were producing very little income, so investment bankers became creative in how they defined profits. Under the guise of comparability, a company with debt (Company X) that was paying interest expense could not be compared on an operational profit basis with a closely related company that operated with NO debt (Company Z). In other words, two identical companies could be selling the same number of widgets at the same prices and have the same cost structure and operating income, but the company with debt on their balance sheet would have a different (lower) net income. The investment banker and company X’s answer to this apparent conundrum was to simply compare the operating earnings or EBIT (Earnings Before Interest and Taxes) of each company (X and Z), rather than the disparate net incomes.

The Advantages of EBITDA

Although there is no silver bullet metric in financial statement analysis, nevertheless there are numerous benefits to using EBITDA. Here are a few:

- Operational Comparability: As implied above, EBITDA allows comparability across a wide swath of companies. Accounting standards provide leniency in the application of financial statements, therefore using EBITDA allows apples-to-apples comparisons and relieves accounting discrepancies on items such as depreciation, tax rates, and financing choice.

- Cash Flow Proxy: Since the income statement traditionally is the financial statement of choice, EBITDA can be easily derived from this statement and provides a simple proxy for cash generation in the absence of other data.

- Debt Coverage Ratios: In many lender contracts certain debt provisions require specific levels of income cushion above the required interest expense payments. Evaluating EBITDA coverage ratios across companies assists analysts in determining which businesses are more likely to default on their debt obligations.

The Disadvantages of EBITDA

While EBITDA offers some benefits in comparing a broader set of companies across industries, the metric also carries some drawbacks.

- Overstates Income: To Charlie Munger’s point about the B.S. factor, EBITDA distorts reality. From an equity holder’s standpoint, in most instances, investors are most concerned about the level of income and cash flow available AFTER all expenses, including interest expense, depreciation expense, and income tax expense.

- Neglects Working Capital Requirements: EBITDA may actually be a decent proxy for cash flows for many companies, however this profit measure does not account for the working capital needs of a business. For example, companies reporting high EBITDA figures may actually have dramatically lower cash flows once working capital requirements (i.e., inventories, receivables, payables) are tabulated.

- Poor for Valuation: Investment bankers push for more generous EBITDA valuation multiples because it serves the bankers’ and clients’ best interests. However, the fact of the matter is that companies with debt or aggressive depreciation schedules do deserve lower valuations compared to debt-free counterparts (assuming all else equal).

Wading through the treacherous waters of accounting metrics can be a dangerous game. Despite some of EBITDA’s comparability benefits, and as much as bankers and analysts would like to use this very forgiving income metric, beware of EBITDA’s shortcomings. Although most analysts are looking for the one-size-fits-all number, the reality of the situation is a variety of methods need to be used to gain a more accurate financial picture of a company. If EBITDA is the only calculation driving your analysis, I urge you to follow Charlie Munger’s advice and plug your nose.

Wade W. Slome, CFA, CFP®

Plan. Invest. Prosper.

*DISCLOSURE: Sidoxia Capital Management (SCM) and some of its clients own certain exchange traded funds, but at the time of publishing had no direct positions in any security referenced in this article. No information accessed through the Investing Caffeine (IC) website constitutes investment, financial, legal, tax or other advice nor is to be relied on in making an investment or other decision. Please read disclosure language on IC “Contact” page.

Cash Flow Statement: Game of Cat & Mouse

Much like a game of a cat chasing a mouse, analyzing financial statements can be an endless effort of hunting down a company’s true underlying fundamentals. Publicly traded companies have a built in incentive to outmaneuver its investors by maximizing profits (or minimizing expenses). With the help of flexible GAAP (Generally Accepted Accounting Principles) system and loose estimation capabilities, company executives have a fair amount of discretion in reporting financial results in a favorable light. Through the appropriate examination of the cash flow statement, the cat can slow down the clever mouse, or the investor can do a better job in pinning down corporate executives in securing the truth.

Going back to 15th century Italy, users of financial statements have relied upon the balance sheet and income statement*. Subsequently, the almighty cash flow statement was introduced to help investors cut through a lot of the statement shortcomings – especially the oft flimsy income statement.

Beware of the Income Statement Cheaters

Did you ever play the game of Monopoly with that sneaky friend who seemed to win every time he controlled the money as the game’s banker? Well effectively, that’s what companies can do – they can adjust the rules of the game as they play. A few simple examples of how companies can potentially overstate earnings include the following:

- Extend Depreciation: Depreciation is an expense that is influenced by management’s useful life estimates. If a Chief Financial Officer doubles the useful life of an asset, the associated annual expense is cut in half, thereby possibly inflating earnings.

- Capitalize Expenses: How convenient? Why not just make an expense disappear by shifting it to the balance sheet? Many companies employ that strategy by converting what many consider a normal expense into an asset, and then slowly recognizing a depreciation expense on the income statement.

- Stuffing the Channel: This is a technique that forces customers to accept unwanted orders, so the company selling the goods can recognize phantom sales and income. For example, I could theoretically sell a $1 million dollar rubber band to my brother and recognize $1 million in profits (less 1-2 cents for the cost of the rubber band), but no cash will ever be collected. Moreover, as the seller of the rubber band, I will eventually have to fess-up to a $1 million uncollectible expense (“write-off”) on my income statement.

There are plenty more examples of how financial managers implement liberal accounting practices, but there is an equalizer…the cash flow statement.

Cash Flow Statement to the Rescue

Most of the accounting shenanigans and gimmicks used on the income statement (including the ones mentioned above) often have no bearing on the stream of cash payments. In order to better comprehend the fundamental actions behind a business (excluding financial companies), I firmly believe the cash flow statement is the best place to go. One way to think about the cash flow statement is like a cash register (see related cash flow article). Any business evaluated will have cash collected into the register, and cash disbursed out of it. Specifically, the three main components of this statement are Cash Flow from Operations (CFO), Cash Flow from Investing (CFI), and Cash Flow from Financing (CFF). For instance, let us look at XYZ Corporation that sells widgets produced from its manufacturing plant. The cash collected from widget sales flows into CFO, the capital cost of building the plant into CFI, and the debt proceeds to build the plant into CFF. By scrutinizing these components of the cash flow statement, financial statement consumers will gain a much clearer perspective into the pressure points of a business and have an improved understanding of a company’s operations.

Financial Birth Certificate

As an analyst, hired to babysit a particular company, the importance of determining the maturity of the client company is critical. We may know the numerical age of a company in years, however establishing the maturity level is more important (i.e., start-up, emerging growth, established growth, mature phase, declining phase)*. Start-up companies generally have a voracious appetite for cash to kick-start operations, while at the other end of the spectrum, mature companies generally generate healthy amounts of free cash flow, available for disbursement to shareholders in the form of dividends and share buybacks. Of course, some industries reach a point of decline (automobiles come to mind) at which point losses pile up and capital preservation increases in priority as an objective. Clarifying the maturity level of a company can provide tremendous insight into the likely direction of price competition, capital allocation decisions, margin trends, acquisition strategies, and other important facets of a company (see Equity Life Cycle article).

The complex financial markets game can be a hairy game of cat and mouse. Through financial statement analysis – especially reviewing the cash flow statement – investors (like cats) can more slyly evaluate the financial path of target companies (mice). Rather than have a hissy fit, do yourself a favor and better acquaint yourself with the cash flow statement.

Wade W. Slome, CFA, CFP®

Plan. Invest. Prosper.

*DISCLOSURE: Sidoxia Capital Management (SCM) and some of its clients own certain exchange traded funds, but at the time of publishing had no direct positions in any security mentioned in this article. References to content in Financial Statement Analysis (Martin Fridson and Fernando Alvarez) was used also. No information accessed through the Investing Caffeine (IC) website constitutes investment, financial, legal, tax or other advice nor is to be relied on in making an investment or other decision. Please read disclosure language on IC “Contact” page.

Measuring Profits & Losses (Income Statement)

So far we’ve conducted an introduction to financial statement analysis and a review of the balance sheet statement. Now we’re going to move onto the most popular and familiar financial statement and that is the income statement. One reason this particular financial statement is so popular is because it answers some of the most basic questions, such as, “How much stuff are you selling?” and “How much dough are you making?” With executive compensation incentives largely based off income statement profitability, it’s no surprise this statement is the one of choice. Unlike the balance sheet, which takes a snapshot picture of all your assets at a specific date in time, the income statement is like a scale, which measures gains or losses of a company over a specific period of time.

P&L Motivations

Like a wrestler or an overweight dieter, there can be an incentive to alter the calibration or lower the sensitivity of the financial weight scale. Fortunately for investors and other vested constituents, there are auditors (think of the Big 4 accounting firms) and regulators (such as the Securities and Exchange Commission) to verify the validity of the financial statement measurement systems in place. Sadly, due to organizational complexity, lack of resources, and lackadaisical oversight, the sanctity of the supervision process has been known to fail at times. One need not look any further than the now famous case of Enron. Not only did Enron eventually go bankrupt, but the dissolution of one of the most prestigious accounting firms in the world, Arthur Andersen, was also triggered by the accounting scandal.

Tearing Apart the Income Statement

Determining the profitability of a business through income statement analysis is generally not sufficient in coming to a decisive investment conclusion. Establishing the trend or the direction of profitability (or losses) can be even more important than the actual level of profits. The importance of profit trends requires adequate income statement history in order to ascertain a true direction. Comparability across time periods requires consistent application of rules going back in time. The “common form” income statement (or “percentage income statement”) is an excellent way to evaluate the levels of expenses and profits on an income statement across different periods. This particular format of historical income statement figures also provides a mode of comparing, contrasting, and benchmarking a company’s historical results with those of its peers (or the industry averages alone).

Shredding through the income statement, along with the other financial statements, often creates insufficient data necessary to make informed decisions. Other components of an annual report, such as the footnotes and Management Discussion and Analysis (MD&A) section, help paint a more complete picture. Interactions with company management teams and the investor relations departments can also be extremely influential forces. Regrettably, corporate viewpoints provided to investors are often skewed to an overly optimistic viewpoint. Management comments should be taken with a grain of salt, given the company’s inherent motivation to drive the stock price higher and portray the company in the most positive light.

Tricks of the Trade

One way to achieve profit goals is to improve revenues. If the traditional path to generating sales is unattainable, bending revenues in the desired direction can also be facilitated under the GAAP (Generally Accepted Accounting Principles) rules, or for those willing to risk times behind bars, criminals can attempt to bypass laws.

Due to the flexibility embedded within GAAP standards, corporate executives have a considerable amount of leeway in how the actual rules are implemented. Covering all the shenanigans surrounding income statement exploitation and distortion goes beyond the scope of this article, but nonetheless, here a few examples:

- Customer Credit: The relaxation of credit standards without increasing the associated credit loss reserves could have the effect of increasing short-term sales at the expense of future credit losses.

- Discounts: Offering discounts to accelerate sales is another accounting tactic. Offering price reductions may help sales now, but effectively this strategy merely brings future revenue into the current period at the expense of future sales..

- Adjusting Depreciation: Extending depreciation lives for the purpose of lowering expense and increasing profits may temporarily increase earnings but may distort the necessity of new capital equipment.

- Capitalization of Expenses: This practice essentially removes expenses from the income statement and buries them on the balance sheet.

- Merger Magic: Merger accounting can distort revenues and growth metrics in a manner that doesn’t accurately portray reality. Internally (or organic) growth typically earns a higher valuation relative to discretionary acquisition growth. Although mergers can optically accelerate revenue growth, acquirers usually overpay for deals and academic studies indicate the high failure rate among mergers.

Faux Earnings: Fix or Fraud?

The nature of financial reports has become more creative over time as new and innovative names for earnings have surfaced in press releases, which are not subject to GAAP guidelines. Reading terms such as “core earnings,” “non-GAAP earnings,” and “pro forma earnings” has become commonplace.

In addition, companies on occasion include GAAP approved “extraordinary” charges that are deemed rare and infrequent items. By doing so, income from continuing operations becomes inflated. More frequently, companies attempt to integrate less stringent, non-GAAP compliant, one-time so-called “nonrecurring,” “restructuring,” or “unusual” items. These “big-bath” expenses are designed to build a higher future earnings stream and divert investor attention to the earnings definition of choice. Unfortunately, for many companies, these nonrecurring items have a tendency of becoming recurring. Case in point is Procter & Gamble (PG), which in 2001 had recognized restructuring charges in seven consecutive quarters, totaling approximately $1.3 billion – recognizing these as part of ongoing earnings seems like a better choice. On the flip side, some companies want to include non-traditional gains into the main reported earnings. Take Coca-cola (KO) for example – in 1997 the Wall Street Journal highlighted Coke’s effort to include gains from the sales of bottler interests as part of normal operating earnings.

The review of the income statement plays a critical role in the overall health check of a company. From a stock analysis point, there tends to be an over-reliance on EPS (Earnings Per Share), which can be distorted by inflated revenues (“stuffing the channel”), deferral of expenses (extended depreciation), tax trickery, discretionary share buybacks, and other tactics discussed earlier. Generally speaking, the income statement is more easily manipulated than the cash flow statement, which will be discussed in a future post. Suffice it to say, it is in your best interest to make sure the income statement is properly calibrated when you perform your financial statement analysis.

Wade W. Slome, CFA, CFP®

Plan. Invest. Prosper.

DISCLOSURE: Sidoxia Capital Management (SCM) and some of its clients own certain exchange traded funds, but at the time of publishing had no direct positions in PG, KO or other securities referenced. References to content in Financial Statement Analysis (Martin Fridson and Fernando Alvarez) was used also. No information accessed through the Investing Caffeine (IC) website constitutes investment, financial, legal, tax or other advice nor is to be relied on in making an investment or other decision. Please read disclosure language on IC “Contact” page.